Borderlines

-

Lara Almarcegui, Rossella Biscotti, Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan, Willie Doherty, Núria Güell, Ruth E. Lyons, Amalia Pica, Khvay Samnang, Santiago Sierra, Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor

Borderlines was a group exhibition that gives form to the conceptual, geo-political, economic and cultural impacts of borders. It draws attention to the ownership of the earth beneath our feet, underwater realms, the rules governing the international movement of goods, nation-states, the UK border in Ireland, financial sovereignty, tribal territories, anarchic polar exploration and the world-wide distribution of natural resources. Conceived to coincide with the UK’s scheduled exit from the EU, Borderlines offers imaginative ways of representing and thinking about frontiers, at a time when very real borders between the UK and Europe are being proposed.

In 2023 we were delighted to be able to extend the thinking of this exhibition through a project with Lara Favaretto. Click here to read about and listen to 'Thinking Head - Clandestine Talk.'

Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan have three works in the exhibition. Monument to Another Man’s Fatherland reflects on the story of the Pergamon Altar. It contextualises the extraordinary frieze (now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin), with the plight of Turkish migrants hoping to enter the EU, just as the repatriation of the Parthenon (Elgin) marbles reappear in public debate as a result of the Brexit negotiations. Another work features tonnes of sugar shown alongside the complex story of the artists’ attempt to trace European sugar exported to Africa and then evade trade tariffs by re-importing it back to Europe as an artistic ‘monument’. The third film work, particularly poignant in the context of the Brexit campaign’s close alignment with the UK fisheries, charts the rise and fall of the Urk (Dutch) fishing community after the inland sea they traditionally fished was dammed to create land for development. Lara Almarcegui explores the ownership of the mineral rights under the cities she works in, unearthing how the land beneath our feet is governed, while Rossella Biscotti’s research, into the implications of her tipping a huge slab of marble overboard into international waters, creates a layered picture of the different frontiers of the sea, demarcated by sunken relics, magnetic fields, distress calls, marine life, oil pipes and national boundaries. A more ancient sea is evoked in the salt bowls made by Ruth E Lyons, which are all carved from salt mined from a deposit that dates back millions of years to the Zechstein Sea; this salt deposit stretches from Ireland to Russia, impervious to the nation-states now crowding the top soil. Willie Doherty reflects on the border where Ireland and Northern Ireland meet, between Derry and Donegal, meditating on the dramatic impact that Brexit might have on otherwise unremarkable points on the road, haunted by memories of the militarised border in place before the Good Friday Agreement. Núria Güell presents a consultancy that offered citizens of the PIIGS nations (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain), bailed out by the EU / World Bank and IMF, the opportunity to perform fiscal disobedience based on the tax avoidance schemes used by the super-rich, commenting on debt, obedience and control within the EU. Amalia Pica makes images from the bureaucratic stamps she has collected as her papers are checked at national borders, while Khvay Samnang interprets his understanding of the Chong people’s embodied knowledge of the land and its regions, recreating movements through collaboration with a dancer used to define tribal territories in Cambodia. Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor show the globe as a patchwork of dominant resources – industries, minerals or labour – and finally, Santiago Sierra places the anarchist flag at the North and South Poles.

Share

Exhibition Guide

Published on the occasion of 'Borderlines' at Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh. Edited by Tessa Giblin.

Texts by Tessa Giblin and James Clegg are available to view below, or download free of charge. A large print guide is also available to download.

Please click on the arrow below to view.

Curator's Intro | Tessa Giblin, Director of Talbot Rice Gallery

This exhibition was conceived to coincide with the UK’s scheduled exit from the EU. Now, as we approach the 29 March 2019 – with confusion and disillusion on every side of the debate – news reports pre-empt any introduction we could write to Borderlines. Dressed in military fatigues and carrying M16 machine guns, actors are protesting the potential of a hard Irish border; fears are voiced of British langoustines, scallops, salmon and prawns rotting in customs at the border; and National Treasures such as the Parthenon (or Elgin) marbles are currently at the centre of a heated debate: are they stolen, or does their appropriation represent a ‘creative’ act – to use the British Museum Director Hartwig Fischer’s controversial word.

Our world is built around different interpretations of ownership and it is therefore cut by a multitude of virtual, physical, bureaucratic, imaginary and psychological lines. As the headlines show, political movements like Brexit bring many of these into focus. But Borderlines also seeks to ask questions about the less apparent or even lesser known territories. The exhibition includes tribal interpretations of the animals and lands of Cambodia, asks us to think about the ground beneath our feet and considers the vastly different timescales connected to its political and geological make-up. Including work by ten international artists or duos, it offers a critical perspective on the conceptual, geo-political, economic and cultural impacts of borders in a way that is unique to art.

Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan

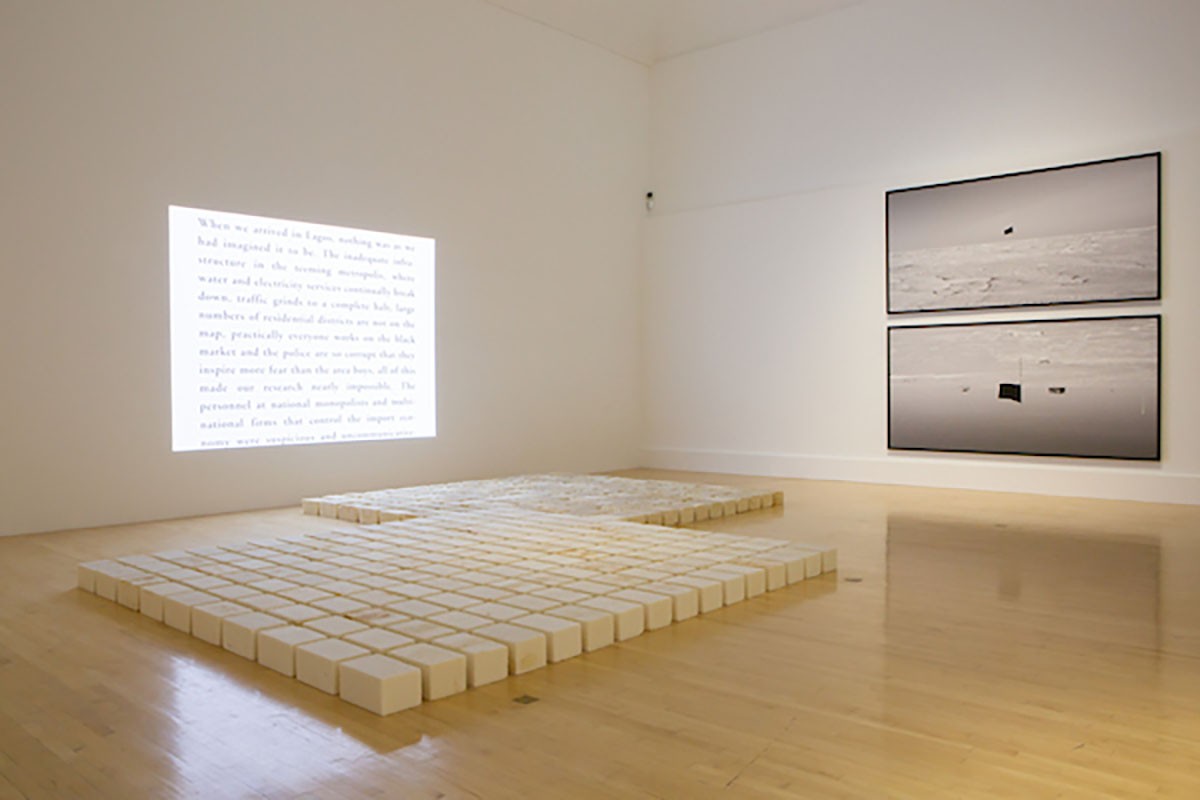

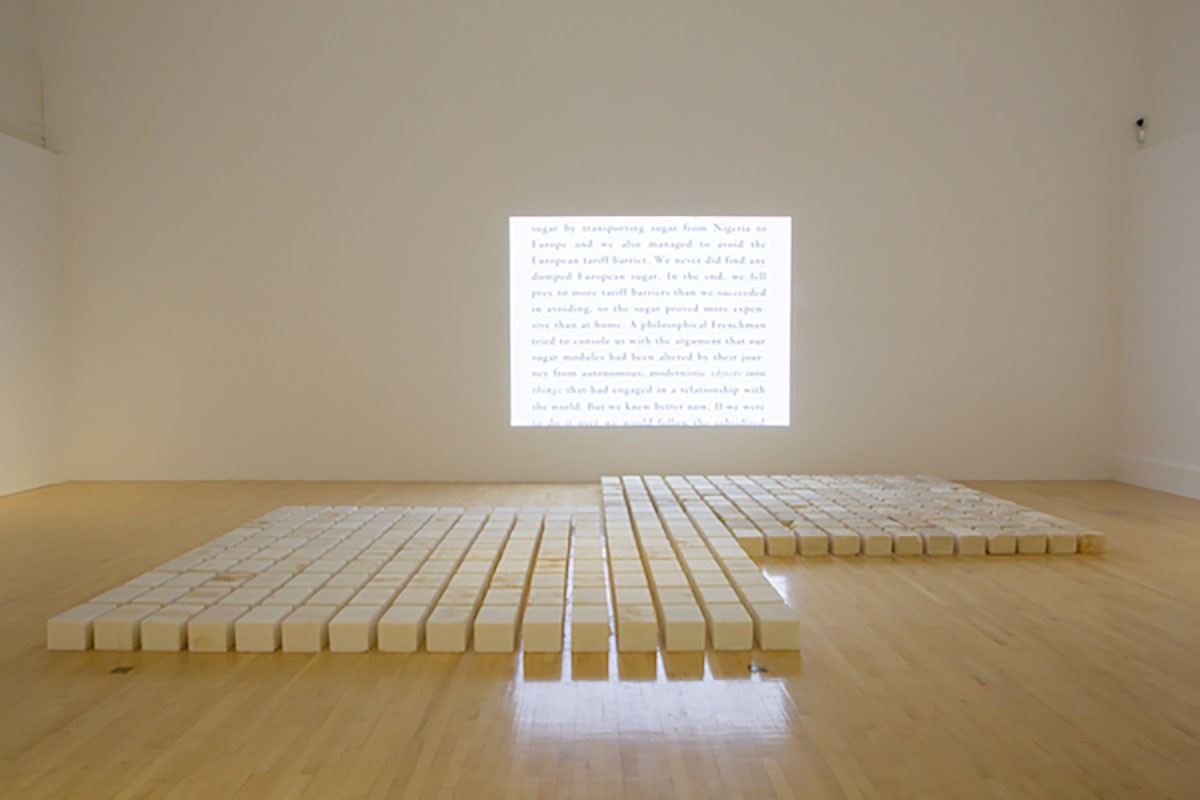

'Monument of Sugar - how to use artistic means to elude trade barriers,' 2007

'Monument of Sugar - how to use artistic means to elude trade barriers' is a sculpture and film documenting the complex evolution of a project in which the artists followed the movement of European sugar.

In 2004 ten countries joined the European Union, significantly expanding its borders. Filming on the day of expansion, in a small village in Poland called Hrebenne, Van Brummelen & De Haan found themselves speaking to a local farmer. As they recount, he showed them sugar and, 'joked that the Polish cukier (sugar) had become twice as sweet since their entry into the European Union.' He was referring to the fact that the value of his sugar had dramatically risen because of the way the EU inflates internal prices, subsidies exports and imposes high tariffs on external imports.

This protectionism has roots in Napoleonic times when new techniques made it possible to extract sugar on an industrial scale from sugar beet, which grows in cold climates. This resulted in France and England creating blockades preventing sugar cane in hot climates using slave plantations.

Van Brummelen & De Haan followed and then responded to stories about large quantities of surplus EU sugar being exported to Nigeria, something they found curious given that the African climate is perfect for growing sugar cane. 'The plan was to turn the flow of sugar around, by purchasing Europe's cheap surplus sugar in Nigeria and shipping it back home. To elude the European trade barrier against sugar imports, we would make use of a minimal artistic intervention to turn the sugar crystals in situ into sculptural blocks, bringing them into Europe as a "monument of sugar" - monuments and original sculptures being exempt from high import tariffs.'

Indicative of the artists' practice, this plan did not take them on a straight journey and they faced many obstacles and difficulties which are documented in the film and became part of the work. In Nigeria, hot and humid weather conditions, a lack of communication systems and disorganized port services slowed their progress. Unable to find the quantities of sugar they had seen on paper leaving the EU, they asked around to discover that Nigeria actually relied upon sugar imported from Brazil. Rather than being able to buy European Sugar they therefore bought Brazilian sugar, which, fortified with vitamins, was not only more expensive but wasn't as easy to mould. The €1000 worth of sugar bulk they purchased in Nigeria provided the material for 144 sugar blocks. These blocks are shown with a second group of 160 sugar blocks - the amount that €1000 could buy in Europe.

The history of sugar cane versus sugar beet continues to influence contemporary politics. Tate & Lyle, one of the most recognized brands of sugar in the UK, import cane sugar from the tropics. They were therefore one of the most vocal advocates for Brexit. Whereas for sugar beet farmers, who produce around 1.4m tonnes of British sugar annually, the prospect of losing EU protection is very troubling.

Santiago Sierra

'Black Flag,' 2015

The photographs shown are part of 'Black Flag', which documents an expedition to plant an anarchist flag at both of the earth’s geographic poles.

‘Anarchism: the name given to a principle or theory of life and conduct under which society is conceived without government - harmony in such a society being obtained, not by submission to law, or by obedience to any authority, but by free agreements concluded between the various groups, territorial and professional, freely constituted for the sake of production and consumption, as also for the satisfaction of the infinite variety of needs and aspirations of a civilized being.’ Peter Alexeyevich Kropotkin, 1910

For a number of years Santiago Sierra has placed black squares around various European cities. Whilst they might evoke the minimal forms of early avant-garde art, for him, ‘The most radical black square on [a] white background … is an anarchist flag on an extremely snowy landscape.’ When conceiving 'Black Flag', Sierra married these forms with the idea of Piero Manzoni’s famous 'Socle du Monde' '[Base of the World]' (1961) – an inverted plinth that playfully claimed to exhibit the world – bookending the globe with the anarchist flag. In doing so, Sierra asks us to imagine what a world – shedding its dependence on hierarchies and being driven by mutual consensus – might be like. Marking the incredibly difficult journey to poles to achieve the work, Sierra also seems to be provoking us to consider that anything is possible.

There is no land at the North Pole, which is an ever changing field of ice. In 2007 however, Russia evoked the idea of ‘planting a flag’ to claim a territory by sending submarines to place a 1 metre high flag two-and-a-half miles under the sea. This created consternation because according to the UN convention, economic rights over that vast region are also jointly owned by Canada, Norway, the US and Denmark. Kristin Bartenstein, a professor of international law has written that the less-reported aspect of the Russian expedition to the North Pole is that it is part of a vast program of scientific research,’ and that ‘The American government agency for geological research (US Geological Survey) estimates that the Arctic seabed contains as much as 22 percent of the world’s undiscovered hydrocarbon resource [and] the Russian Federation, Norway, Denmark, the United States, and of course Canada have all been busy for several years gathering the information necessary to buttress their respective claims to the submarine Arctic expanses. Global warming, which renders the environment potentially less hostile … increases the value of the claims.’

The Antarctic was designated a scientific preserve in 1959 through the Antarctic Treaty. The national flags of the original signatories of the treaty – Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, South Africa, United Kingdom and the United States – stand by the Ceremonial South Pole. However, the treaty has since been ratified by 53 nations and since 2002 the Antarctic has had its own non-national flag. The sometimes overlapping claims on territory prior to the treaty, by Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom, were effectively put on hold. Crucially the treaty states that freedom for scientific investigation will continue and that all discoveries shall be exchanged and made freely available to all. The research done as part of Polar Science is vital to our understanding of climate change, a principally pan-national concern.

Sierra considers 'Black Flag' to be his most beautiful work, much of his previous practice demonstrating the ugliness of the exploitation inherent in the capitalist system. He states, ‘Flags, national anthems and all of that garbage comply with a despicable ideology that defines people in the same way that a red-hot branding iron defines livestock. The black flag is the flag of all of us who don’t identify with a flag or don’t want to have a flag, something to visually set against the multiple colours of the patriotic cloths.’ Shown recently at DCA, Dundee, its back-to-back showing at Talbot Rice Gallery also speaks of a shared commitment within the arts community to pose critical questions about territory and ownership.

Willie Doherty

'Between (Where the Roads Between Derry and Donegal Cross The Border),' 2019

'Between (Where the Roads Between Derry and Donegal Cross The Border)' is a portrayal of the 20 points between County Donegal and the City of Derry where roads cross the border separating the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Living in Donegal and working in Derry, Willie Doherty crosses this border on a daily basis. He knows farmers who have land on either side and many people who – like him – live across the lines. The memory of what it was like when it was militarised, before the Good Friday Agreement (1998), still haunts these now seemingly inconsequential points in the road. Doherty remembers how quickly the checkpoints were dismantled in the mid-1990s once the British Prime Minister, John Major issued the order for them to be removed; he is therefore acutely aware of how quickly a political decision can take effect and how quickly they might be resurrected. Coupled with custom checks – in place until 1993, when the introduction of a single market for EU member states made them unnecessary – the hard borders not only impeded movement, but were a provocative symbol of British intervention in Ireland that led to fatal clashes.

Whilst there are hundreds of points crossing between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, this particular part of the border also tells another story. Whilst the border created in 1921 follows the River Foyle further south, it takes a turn to accommodate Derry’s historic city walls.

Derry was part of Donegal until around 1610, at which point the English – having assumed control of the ‘kingdom’ since the reign Henry VIII – signed it over to become part of the Plantation of Ulster. This project, to settle English-speaking, protestant, and loyalist people in Ireland, principally English and Scots, resulted in many Irish people losing their lands, whilst creating an enduring community with ties to the future British mainland. The city wall of Derry, which the border follows, therefore traces a clear, colonial history.

The words within the prints evoke some of Doherty’s earlier works, made during the Troubles. Overlaid image with text, they often offered elliptical messages that spoke to the irresolution and complexity of the situation in Ireland. 'Waiting' (1988) for example, shows the sun setting over some squat brutalist buildings in Derry. A mural in the background announces, ‘You are now entering Free Derry’ whilst Doherty’s overlaid text reads: ‘GOLDEN SUNSETS’ and ‘WAITING’. Like this new work it gives a sense of the problematic nature of imagining a ‘free’ Derry.

Now, Brexit seems to have created its own elliptical language, one that hinges on a number of irresolvable oppositions. For Fintan O’Toole, Brexit derives from an attitude of self-pity that is still colonial in essence. ‘Perhaps,’ he writes in his book 'Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain', ‘empires don’t quite end when you think they do. Perhaps they have a final moment of zombie existence. This may be the last stage of imperialism – having appropriated everything else from its colonies, the dead empire appropriates the pain of those it has oppressed.’ It is in this context, looking at banal locations that are so politically charged – and appropriating the rhetoric of Brexit – that 'Between (Where the Roads Between Derry and Donegal Cross the Border)' resonates, proffering the enigmatic words: ‘BETWEEN THE FUTURE AND THE PAST’, ‘BETWEEN DELUSIONS AND DREAMS’.

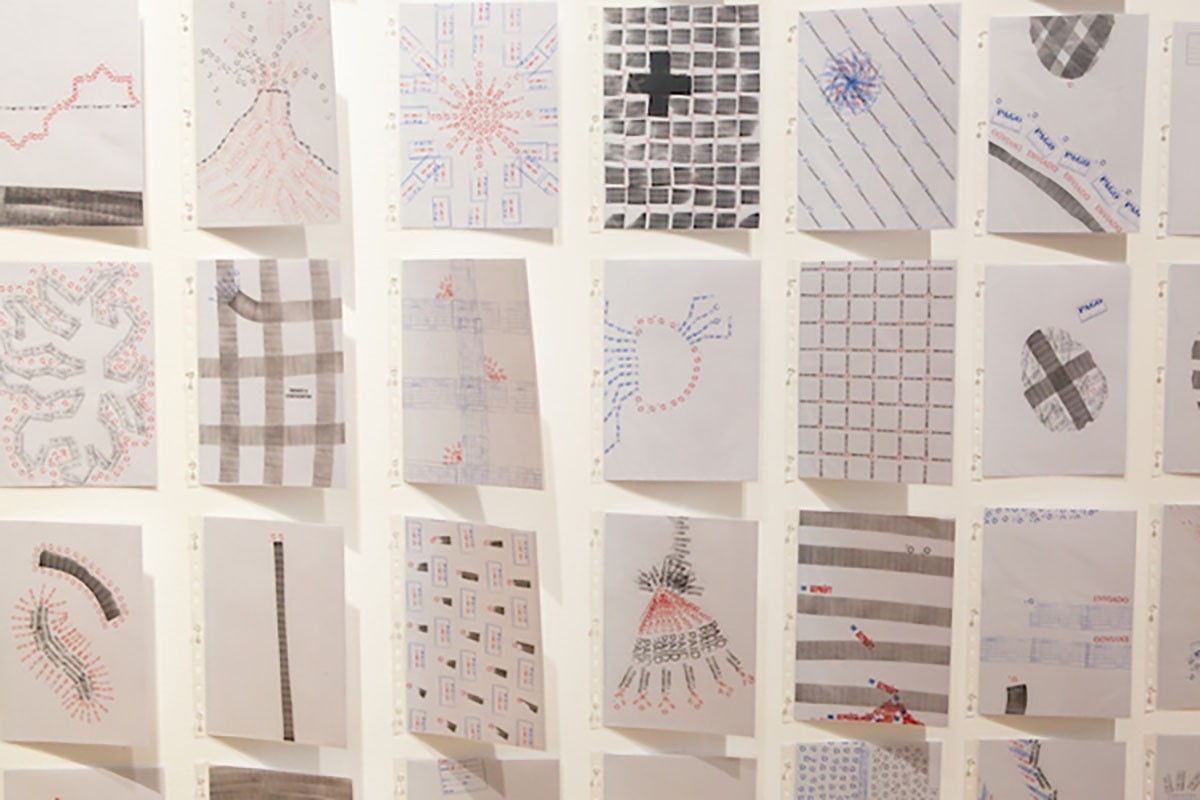

Amalia Pica

'Joy in Paperwork,' 2016

'Joy in Paperwork' was created by Argentinian, now British- Argentinian, artist Amalia Pica in response to the oppressive bureaucracy of applying for British citizenship.

As a non-EU national, Pica had to undergo a lengthy process so that she could live and work in London, with endless forms to fill in, phone-calls to make and conversations to have with her immigration lawyer. Being an artist applying for citizenship can be particularly challenging. Pica had to get letters from the curators, galleries and institutions she worked with to help to prove how she made her income, putting embarrassing pressure on professional relationships. As she commented, ‘the Home Office has a hard time understanding what artists do for a living, how we earn our income, and why we spend such little time at home.’ Reflecting more broadly she says, ‘We have buried ourselves in this bureaucratic machine that makes us feel quite suffocated, so what I wanted to do with this series of works was to inject joy into paperwork. Pretend it was a fun thing to do.’

Pica recalled playing with stamps as a child in her mother’s office and so asked friends from around the world to collect and send her official stamps. They came in many different languages, all designed to officially declare that something had been paid, received or delivered; they distinguished between originals and copies.

Reflecting on Pica’s first retrospective in 2013, critic Ruby Beesley said that, ‘Perhaps the most important element of Pica’s work … is her exploration of language and how languages that have been created in both organic and more contrived circumstances (and which are viewed as an important and dominant signifier of civilisation) can be turned into something nonsensical, almost silly.’ Finding her element, the joy, within the stamps, Pica was able to start creating new systems from her collection of officious fragments, quickly generating thousands of versions of a new kind of paperwork. At first creating grid- like forms, she gradually began to make looser patterns and figurative forms, playing with the colours and meanings of her invented system.

In contradiction to the tightening of immigration control, more and more people are crossing national borders. As Bridget Anderson, Nandita Sharma and Cynthia Wright stress in their editorial for 'Refuge', this apparent contradiction reflects a system that is exerting greater control over the rights of both immigrants and citizens within a country. ‘Any study of national borders needs to start with the recognition that they are thoroughly ideological. While they are presented as filters, sorting people into desirable and non-desirable, skilled and unskilled, genuine and bogus, workers, wife, refugee etc., national borders are better analysed as moulds, as attempts to create certain types of subjects and subjectivities… They place people in new types of power relations with others and they impart particular kinds of subjectivities.’

Once asked what is art, Pica responded, ‘It’s a way of resisting the lack of meaning in things, a desperate attempt to make sense of how random and absurd the world is - and it’s also a way of celebrating exactly that.’ In 'Joy in Paperwork', we might see this approach in her way of intuiting and disengaging with the insidious power relations implied in the process of applying for citizenship; the use of official stamps as a bid for freedom.

Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor

'Le monde et les choses,' 2014

'Le monde et les choses' is a map based on statistics published by the CIA, showing the ‘dominant industries’ of different countries across the world.

Vatamanu & Tudor brand the CIA’s reductive depiction of the world’s industries and resources as being a reflection of ‘the latest stage of colonialism’. The map, with a title translating as the world and the things, shows that the United States boasts Capital Goods, Aircraft, Motor Vehicle Parts, Computers and Telecommunications. These ‘advanced’ or ‘technological’ products are reflected across Europe and in China whilst the Middle East, large parts of Africa and Russia are noted only for their Oil and Petroleum products, with other countries listing valuable materials like Gold or Diamonds.

Gaining control of these goods – particularly oil – has been a key part of American policy since the Cold War. Struggles in places like Iraq have been part of a strategy by the US to reduce Europe’s dependency on Russian oil supplies, whilst its intervention in the Pacific aims at exerting some control over China’s economy. As Michael Lind writes for 'The Spectator', ‘The end of the Cold War left America’s leadership wondering how to justify the US military protectorates over western Europe and Japan. The 1990 invasion of Kuwait by Saddam [Hussein] provided the answer: instead of temporarily protecting its European and East Asian allies from the Red Army, the US would henceforth perpetually protect them from other threats, including the disruption of the oil supplies on which their economies depended. By policing critical regions like the Persian Gulf on behalf of all industrial nations, Washington hoped to forestall re-armament and unilateral scrambles for security, including energy security, by the other great powers.’

The simple, almost childlike quality of the fabric representation of 'Le monde et les choses' therefore belies a long-term US strategy that amounts to nothing less than a bid for world dominance.

It is through a manipulation of markets, transport routes and access that it has attempted to exert its power across the world. The artists appropriate the flattened map of the globe, and replace the names of nations with their ‘productivity’ as considered by the CIA. Here, nation-states are eschewed in favour of raw material or the products of human labour, and the globe becomes of a patchwork of resources rather than a jigsaw puzzle of sovereign territories.

The entry for the United States in the CIA’s online World Factbook states, ‘Buoyed by victories in World Wars I and II and the end of the Cold War in 1991, the US remains the world’s most powerful nation state. Since the end of World War II, the economy has achieved relatively steady growth, low unemployment and inflation, and rapid advances in technology.’ Reflecting this against Vatamanu & Tudor’s map – which divides the world up as resources to be mastered – we might reflect on the resource-based struggles and conflicts that are omitted from this account of global conquest.

![Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan, 'Episode of the Sea', 2014. 35mm film [digital transfer], 63 min. Installation view, Borderlines, 2019. Image courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh.](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2019-04/1G7A1546-Edit_0.jpg?itok=jr7JnvYx)

Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan

'Episode of the Sea,' 2014

'Episode of the Sea' follows the fortunes of the Urk (Dutch) fishing community, from the large-scale land works that have cut them off from sea waters, to their contemporary struggles within the EU and in the global market place.

Van Brummelen & De Haan’s film opens with Urk women standing upon land that was once the sea surrounding Urk, an island that had its own language, culture and economy based on fishing. They recount the ecological consequences of the Zuiderzee Works – a massive project of dikes and dams made to reclaim land from the sea, principally for agriculture, which cut Urk off from the North Sea. Over a number of decades the seabed behind Urk was then gradually filled in, ending its status as an island. The government expected the fishing community to turn to working the land, but instead they got new boats that could take them further out to sea where they could continue to fish. As skilled fishermen the Urkers had great success, and as the film tells, ‘within a few decades every fisherman in the village, from the captain to the lowly deckhand was earning the salary of a secretary of state.’

The Urk fishermen were accepting of Van Brummelen & De Haan, who collaborated with them for two years, because they felt that fishermen, like artists, were both outsiders. The film recounts the adjustments the artists had to make in order to adapt to the conditions at sea and continue filming, always standing near the edge of the boat in case they would be sick. They shot the film on 35mm film, likening the consumption of materials and technologies in image making to the expenditure of materials required by the fishing trawlers, the fuel used in the pursuit of a catch, and the need to implement new techniques to be able to survive.

The fishermen recount the differences between the community spirited Urk industry – which shares profits and good fishing spots – to one increasingly governed by bureaucratic procedures. After the UK lost out to Iceland in the ‘cod wars’ the EU gave priority to UK fishing vessels in the North Sea, making it very difficult for the Urkers to fish and raising questions about their futures. Adapting again, the Urkers started to fish using British Fishing rights. In recent news one Dutch fisherman claimed that if you, ‘eat fish and chips in England [there is a] sixty percent chance the fish was delivered by Urkers.’ Brexit, which the Urk fishermen fear is a sign that the British want to confiscate their rights and effectively create a border at sea, is therefore a challenging proposition that runs counter to the long history of shared fishing. As one of them phrased it, ‘fish don’t recognise borders.’ In the UK more broadly, the industry is dominated by a few families who – as a Greenpeace investigation found – control over thirty percent of fishing quotas and regularly appear on the Sunday Times Rich List. The report states that, ‘while it points the finger at others, [the UK] government is to blame for a sector rigged in the interests of the super-rich. Any future fishing policy must consider how new and existing quota can be more fairly distributed…’. So, whilst the fishing industry has been at the forefront of the pro-Brexit campaign – with Nigel Farage sailing up the Thames in a fishing trawler a week before the referendum – it is apparent that unless the actual distribution of fishing quotas is also addressed, smaller fishing communities will continue to struggle.

Ruth E Lyons

'Salarium,' 230 million BCE-ongoing

'Salarium' consists of a series of bowls made from salt extracted from the deposits of a vast sea that existed 230 million years ago. The Zechstein Sea is thought to have been an epeiric sea, that is a shallow sea covering the central area of a continent.

Whilst the residual layer of salt runs from Northern Ireland to Poland, the world would have looked very different 230 million years ago. Then, the super continent named Pangaea was still intact, with modern day Europe adjoined to the landmasses that became North America and Africa. Ruth E Lyons worked with salt mines across Europe that extract salt from the Zechstein deposits. The colour of the salt changes across the continent, being pink in Germany and white in Poland. This includes a mine in Carrickfergus, which is Northern Ireland’s only salt mine. Of the 500,000 tonnes of ancient salt mined there every year, much of it is supplied as rock salt for use on roads, meaning the mine’s fortunes are tied up with the seasonal timescales of winter weather.

Salt is deeply implicated in the growth of human civilizations. As Mark Kurlansky writes in Salt: A World History, ‘salt is so common, so easy to obtain, and so inexpensive that we have forgotten that from the beginning of civilization until about 100 years ago, salt was one of the most sought-after commodities in human history.’ Salt has been used across the world for the preservation of food, becoming a symbol of permanence in many different cultures. Once dissolved in water it can be distilled again, as the Zechstein Sea proves. Lyons is interested in this liminal property, also seeing her collaboration with the salt industry as an integral part of the work. She writes: ‘Salt is hygroscopic by nature. It has a need to absorb water, in essence to return to being the sea. Given this property, the vessels are unusable objects. Rather they are hosts, a symbol of openness and a meditation on the extraordinary world of little things, conveying the idea of the sea contained in a salt crystal.

'Salarium' is made possible and facilitated by EU Salt, an umbrella association for European salt workers. Following an initial expression of interest in the concept of the project, EU Salt have supported 'Salarium' through an annual commission of salt carvings that serve as awards and gifts for presenters and exemplary mines at their annual GA Salt summit. In this respect the economy of 'Salarium' has become an essential structural element in the project, which is not simply a facilitating force, but a conceptual cornerstone to its formation.’

Lyon’s bowls balance fragility and timelessness. The paradox within them can be understood in the purpose of the bowls themselves, as to fill them with liquid, as the artist points out, would be to destroy them. This is also felt in our own bodily relationship to salt water: drink it and we will die, yet salt water makes up much of our bodies.

On the other hand – by extension to the Zechstein sea – they call to an ancient underground territory that crosses and vastly pre-dates European nation states. As Rana Dasgupta wrote recently, ‘Europe, of course, invented the nation state: the principle of territorial sovereignty was agreed at the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 … [making] large-scale conquest difficult within the continent; instead European nations expanded into the rest of the world.’ Floating on an illuminated plinth, Lyon’s bowls offer a link – at a very human scale – to a geological perspective that dwarfs the borders and time spans that people have so fatally contested.

Rossella Biscotti

'The Journey,' 2016

'The Journey' contemplates the consequences of dropping an object into the Mediterranean Sea, exploring the multitude of different territories it would become embroiled within.

Rossella Biscotti has often used her multi-layered practice to consider the complex histories of sites and materials around the world. In 2010 she won an international art prize during The XIV International Biennale in Carrara and was awarded a piece of the famous marble favoured by Michelangelo, and also used to construct some of the most iconic buildings of the Roman Empire. Using the proposition that she would drop it into international waters to drive a new project, Biscotti set about researching the geopolitical make-up of the Mediterranean, between Italy, Tunisia, Libya and Malta.

Whilst we might imagine the sea to be a fluid space, her research shows how many borders congregate under the waters, revealing military control, oil and gas reserves which are licensed to various companies, pipelines, shipwrecks, trading routes, national territories, magnetic fields and incidences of migrant distress calls. Her aim was to show how complex this territory is, with each element of the work proposing another layer and another reading of the same space. The yellow line running through the installation corresponds to the specific line of latitude Biscotti is considering for the submersion of her blue marble block. It also functions as a marker that allows us to locate ourselves within these different cartographies.

One blueprint records World War II shipwrecks under the water. The Mediterranean was considered to be of strategic importance to Winston Churchill, who wanted to preserve trade routes and access to countries like Egypt, explaining the number of British submarines stationed there. Worldwide there are thought to be as many as 3 million shipwrecks.

Any human remains under the sea that date back over 100 years are considered to be relics and are protected by the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.

In a sense, these casualties of war await that status, whilst Biscotti’s block of marble will have to wait a century before becoming a relic. The second blueprint refers to the depth of the water, as if describing an inverted mountain range. It lists specific areas such as the Tunisian Plateau and notes geological features including magnetic areas and a ‘jurassic cretaceous composite’, that is rock formed between 145-65 million years ago.

In a one-month period, there were 375 distress calls made in this area alone, the co-ordinates of the calls documented in the pile of papers within the installation. During the ongoing refugee crisis, the Mediterranean has seen huge numbers of people attempting to cross from Africa into Europe to seek asylum or better economic prospects. A divisive subject within Europe, it is related not only to exclusive immigration laws favoured by many behind the UK’s pro-Brexit lobby, but also to a longer global history. As Daniel Trilling put it, ‘Thousands of people from former European colonies, whose grandparents were treated as less than human by their European rulers, have drowned in the Mediterranean in the past two decades, yet this only became a “crisis” when the scale of the disaster was impossible for Europeans to ignore.’

'The Journey' also considers the marine environment, with the Mediterranean Sea being considered one of the world’s richest ecosystems. Due to environmental changes, including huge landscaping projects such as the continually expanding Suez Canal, the ecology of this area is changing at an alarming rate. This includes the rise of non-indigenous species, which are documented in the slide show of images, and monitored daily by the various governments. As always, Biscotti is interested in finding points where different systems for constructing meaning collide. 'The Journey' intentionally preserves a kind of aesthetic, factual distance from the information it presents, accruing parallel readings rather than offering a singular narrative line. In this way it suggests how impossible it is to make sense of the true complexity of different regions, subject as they are to a multitude of competing territories.

Lara Almarcegui

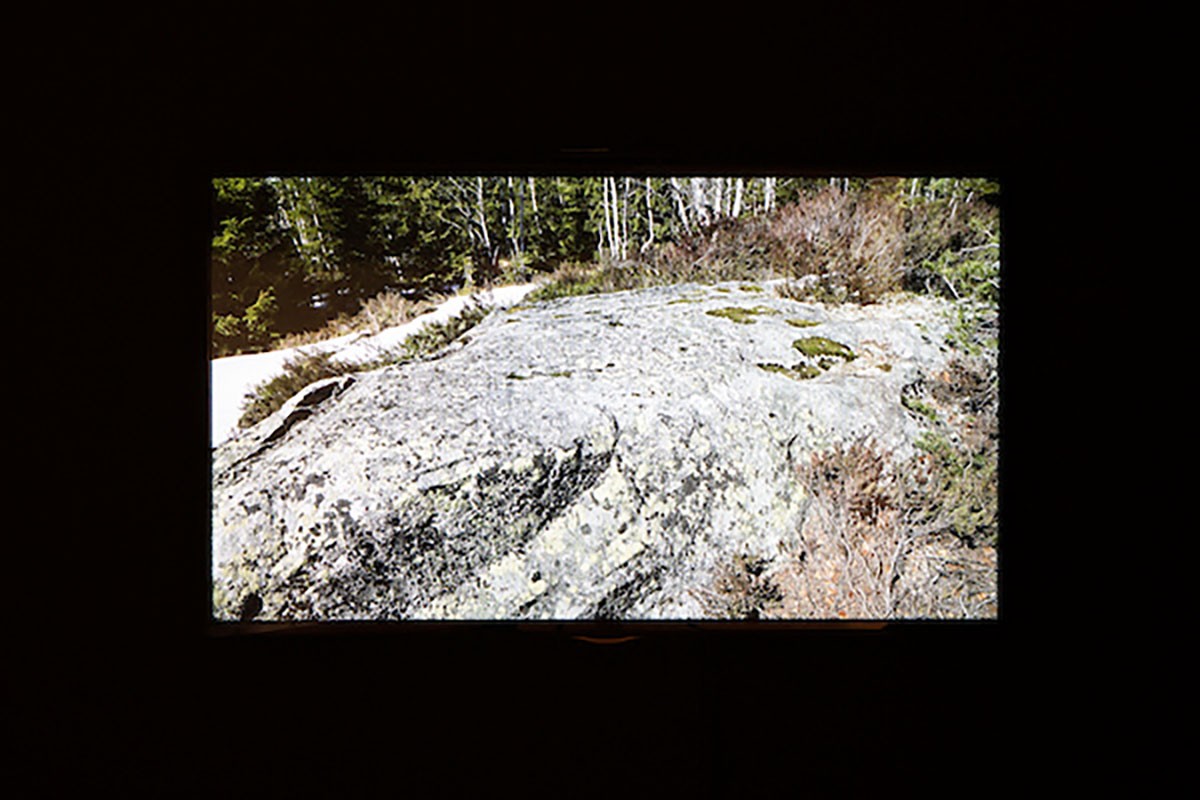

'Mineral Rights (Tveitvangen),' 2015

'Mineral Rights (Tveitvangen)' is a slide show that reflects part of an ongoing project to explore and acquire iron deposits around the world.

Almarcegui’s practice is concerned with understanding the rules governing the built environment. With 'Mineral Rights' the question is directed to the very foundations of the places the work is exhibited in, specifically, who owns the ground beneath them? Successful in securing rights in Tveitvangen, near Oslo, Norway and near Graz, Austria, Almarcegui effectively acquired the right to explore a one kilometre area in these places that, legally, runs from the subsoil to the very centre of the earth.

The Norwegian story, shown in 'Borderlines', connects the vast geological timescale of the iron being deposited 270 million years ago with its discovery by German and Swedish prospectors a mere 400 years ago. Almarcegui’s rights do not equal land ownership, but give her up to nine years to search for minerals. Though not always successful, the process of trying to obtain rights in different places has helped Almarcegui learn about how territories under the earth are governed: discovering that while the Irish state owns most of Ireland’s ‘underneath’, Shell, the British-Dutch oil and petroleum company, owns the resources under the Dutch Government buildings in The Hague.

Edinburgh is built on top of two contrasting types of rock, sedimentary rock accumulated from the deposits of rivers and shallow seas some 300 million years ago, and igneous rock formed from cooled pockets of magma. Coal seams constitute one of the most valuable resources under the city, with a number of buildings having old mineshafts under them.

With Almarcegui, Talbot Rice Gallery worked to purchase mineral rights in Scotland, which proved to be complicated. Firstly, by the fact that landownership and mineral ownership can exist independently, meaning that the deeds conferring ownership of mineral rights cannot necessarily be traced to landowners and might be tied up in ancient grants.

Secondly, information related to landownership in Scotland is notoriously difficult to uncover, as Andy Whiteman, who has been studying the subject for decades says, ‘it is easier to find out the ownership of land in 1915 than it is in 2018.’ Then there is also the fact that certain resources are held in the ‘national interest.’ The Crown in Scotland owns most of the gold and silver, whilst oil and petroleum are managed by the UK government through the Department of Energy and Climate Change, with rights to coal being conferred from Scotland to the UK in 1942 to be held by the Coal Authority.

How revenue from coal sources in Scotland is collected and redistributed by the Treasury has been a source of some conflict – with revenue not being given back to Scotland to pay for the restoration of sites used for surface mining. A 2014 Scottish government report advised that, ‘the degree of “disconnect” between coal revenue and expenditure [is] unacceptable and within the context of devolution … it would be more appropriate for Scotland’s coal reserves to be owned by Scottish Ministers and the licensing responsibility to be devolved to the Scottish Government.’ However, even with devolution, as accorded by the Scotland Act 1998, the Crown Estate in Scotland, which is controlled by Westminster, would still own, ‘mineral rights and other rights reserved by the Crown over the former crown lands, including Edinburgh Castle and other prominent sites.’

The slow progression of slides in 'Mineral Rights' – images of surface terrain interspersed with passages of information – invites us to reflect more upon the make-up of the landscape around us. From rocks that are billions of years old, to the relatively recent human endeavours to map, control and own the world’s resources.

Núria Güell

'Troika Fiscal Disobedience Consultancy,' 2019/2019

'Troika Fiscal Disobedience Consultancy' is a project proffering advice for financial disobedience in the face of the divisive consequences of national debt. In 1992 the Maastricht Treaty (also Treaty on the European Union) was signed, creating the ‘European Community’ and paving the way for the single currency. To create stability and a fair internal market the treaty stated that the community must be compliant with the principles of ‘stable prices, sound public finances … and a sustainable balance of payments.’ It also included a ‘no bail-out’ clause, stating that national debt would remain a national concern.

The financial crisis in Greece saw a profound shift in attitude, with EU nation states offering Greece a €100 billion bailout in 2010. This was followed by a second €130 billion bailout in 2012. Both loans were managed by the Troika, a three-part decision- making body composed of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

In order to meet the criteria of the loans the Troika required strict economic reform that entailed severe austerity measures. These measures dismayed the Greek people, who took to the streets in protest, three losing their lives on 5 May 2010. Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Cyprus were also drawn into what became known as the European Debt Crisis.

The aggressive control exerted by the Troika – whose representatives clashed abrasively with national ministers – is highly controversial. The potential broader political consequences are expressed by Güell through the Troika Fiscal Disobedience Consultancy website: ‘In relation to the Troika, neither the people nor the individual states of the European Union are sovereign. Economic rescue is being accepted at the loss of popular sovereignty.

The exchange currency of these alleged ‘rescues’ comes in the form of neoliberal control, wage cuts, pension cuts, tax increases, layoffs, and all kinds of privatisation. It is the citizens of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Cyprus who are paying for the systemic problems of the economy and the mistakes that were made by financial institutions. The treaties of the European Union have fuelled the rise of the extreme right, and have become a means to override democratic control over production and distribution of wealth.’

Politicians have compared the impact of the Troika to colonialism. In Ireland in 2015, Taoiseach Enda Kenny said the arrival of the central bank was like a ‘bloodless coup.’ Whilst economist and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis once called it a ‘debt colony’. More recently he stated that, ‘I have maintained … that Greece is caught up in a crisis of Europe’s overall design. Greece imploded because it was entangled in a European design that could not survive the aftershocks of the Crash of 2008.’ The impossible repayments led to an ongoing external control of Greek governance.

Through a coffee table display, Güell reminds us of successful acts of resistance, including the Boston Tea Party (1773), Gandhi’s Salt March (1930) and the Montgomery bus boycott (1955). Visitors welcomed into the ‘consultancy’ will notice six clocks on the wall, representing the nations bailed out by the Troika to whom the Troika Fiscal Disobedience Consultancy is open for business, and they might also appreciate the vase of tulips – Europe’s first example of a financial bubble being the Dutch tulip fever of the 17th century. Crucially however it also offers a pragmatic approach to fiscal disobedience, issuing invoices to participants that could enable them to avoid the payment of tax on a fixed sum of money. As the website outlines, a small cut of the sum will go towards the creation of a network of disobedient entities, which will fight against the hierarchies and inequalities hidden within the system of debt.

Khvay Samnang

'Preah Kunlong (The way of the spirit),' 2017

'Preah Kunlong (The way of the spirit)', represents the embodied ‘counter-mapping’ of tribal territories used by the indigenous Chong people of Cambodia.

Khvay is concerned with how capitalist projects damage the people and environment of his native Cambodia, making work to give voice to the communities who are being forced off their land and having to give up their ways of life. He previously made work to highlight how the lakes of his home province of Phnom Penh have been filled with sand to make way for private developments, resulting in thousands of families being evicted. Now, the proposed Cheay Areng Dam project – which would principally provide power to neighbouring countries – threatens to profoundly change the Areng Valley, the site of the largest remaining rainforest in Southeast Asia and the home of the Chong people.

The Chong people are a small indigenous group who share an endangered language and maintain a special relationship to the land. Living with them for a year, and through observation, participation and the making of objects, Khvay grew to understand that their knowledge of the land grows from a fundamentally embodied process. Drawing upon ancestral and oral histories, the Chong people perform rituals in order to understand the spiritual territories of the Areng Valley, establishing tribal borders through elaborate ceremonies each year.

Hendrik Folkerts, the curator Khvay worked with for documenta 14, writes: ‘the practice of cartography is inextricably connected with militarist and colonial histories. These histories dictate that to map land is to own it, that to draw the lines that signify borders, frontiers, and state lines is to align the future terms of power. Political ecologist Nancy Lee Peluso put forward the alternative of “counter-mapping,” providing a method of critical cartography that has aided Indigenous forest users, predominantly in Southeast Asia, to strengthen their claim on their land and its resources by defying dominant instruments of mapmaking.’

Working with long-term collaborator Nget Rady, a choreographer and dancer, Khvay made a film to express what he had learnt about the Chong people’s relationship to particular animals and parts of the land. It is an intimate portrait of a way of understanding borders that is fundamentally resistant to the spatial mechanisms of colonial and capitalist power. It subverts ideas of ownership, quantification, measurement and externality. Given what curator Erin Gleeson has said, that ‘almost everything [Khvay] has documented has disappeared or is about to be gone,’ Preah Kunlong (The way of the spirit) is deeply moving, its combination of strength and fragility lending the work an incredible sense of urgency.

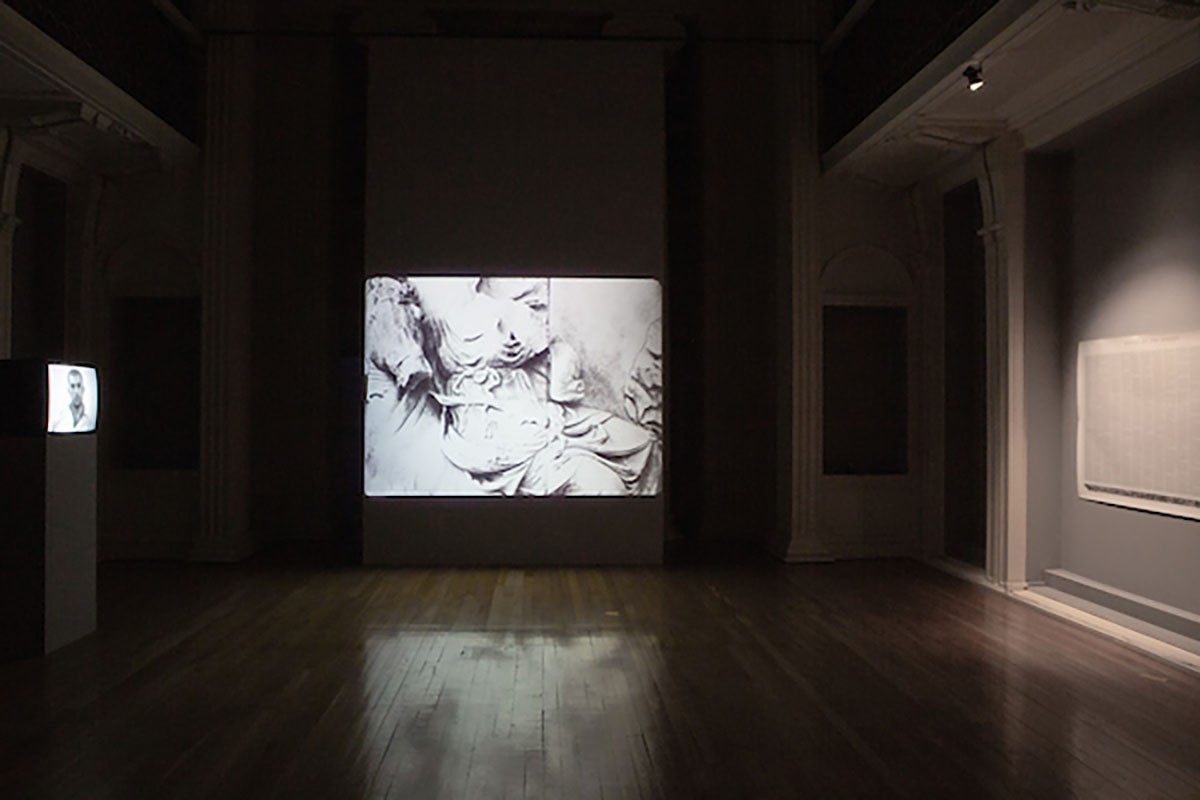

Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan

'Monument to Another Man’s Fatherland: Revolt of the Giants - reconstructed from reproductions,' 2008 – 2009

'Monument to Another Man’s Fatherland' consists of two parts, the films 'Revolt of the Giants - reconstructed from reproductions and Revolt of the Giants - recited by prospective Germans'. Together they create a dialogue between the remarkable frieze on the Pergamon Altar, now held in a museum in Berlin, and the plight of Turkish migrants hoping to emigrate to Germany.

Pergamon was a powerful ancient city located in modern-day Turkey. At one point a vassal of the Seleucid kingdom – part of the disintegrated kingdom of Alexander the Great – it adopted and aspired to many Hellenistic (Greek) styles, the huge altar piece once part of its revered acropolis (or ‘upper city’). Dating back to the 2nd century BC the altar is thought to have been so large that it would have accommodated a 20m wide staircase.

The surviving frieze, which adorned its base, is 113m long and depicts a battle between the Giants and the Olympian gods, an important aspect of Greek mythology known as the Gigantomachy. This battle was frequently depicted in classical art. By the time of the Pergamon Altar – which was made to commemorate a victory over the Celtic Galatians – the Giants were often depicted as monstrous part-animals. The frieze was rediscovered by German engineer Carl Humann. Recognising the significance of this huge find (and its potential jeopardy as the site was being used for quarrying) the newly formed German Empire (1871) took possession of the frieze for the sum of 20,000 German marks. This was part of a drive by the Empire to build collections that would match those of other European powers who were building museums to augment their own sense of status and identity.

Van Brummelen & De Haan were interested in filming the frieze in order to explore the complex history of displaced objects and people, imperialism, ancient homelands and cultural appropriation. However, the Pergamon Museum did not want to be drawn into a project that might ‘stir the debate about repatriation.’ It therefore denied them permission to film and refused access to its image archives. In response, Van Brummelen & De Haan took hundreds of images from guidebooks and academic books and reconstructed the entire frieze, filming it to create a slow, intimate portrait of the object. Shown alongside a poster that details all the sources from which the images, of varying quality, were taken, it highlights the constructed nature of seeing.

The second part of 'Monument to Another Man’s Fatherland' is a film Van Brummelen & De Haan shot in Istanbul, with Turkish people seeking to emigrate to Germany and needing to pass a German integration exam at the Goethe Institute. This difficult language test is a pre-requisite for permanent residency or citizenship and if you don’t achieve a certain level after 600 teaching hours you are denied access. Van Brummelen & De Haan asked the Turkish students participating in a German integration course to read German descriptions of the scenes from the Pergamon frieze. Speaking directly to a 16mm camera, whilst grappling with difficult pronunciation and terms that are not taught in the course, the aspirant migrants describe the sculptural battlefield in their fledgling German, layering today’s movement of migrants onto the historical story of cultural appropriation.

With Brexit, the issue of appropriated cultural artefacts is being revisited, with the Greek government looking to begin a dialogue with the UK about the Parthenon (Elgin) Marbles. Brought to Britain in the early 1800s and inspiring a revived interest in classicism they have played a key role in national identity, yet many in the UK and Greece consider them stolen.

As Brexit will require the support of all 27 member states, their repatriation could become a necessary point of negotiation. Surrounding Edinburgh College of Art’s Sculpture Court are the earliest known casts of these Parthenon marbles. Second generation casts, used as teaching tools, have been included in the exhibition, shadowing Van Brummelen & De Haan’s story of cultural repatriation and reproduction within 'Borderlines'.

![Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan, , Borderlines, 2019. Image courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh. 'Episode of the Sea', 2014. 35mm film [digital transfer], 63 min. Installation view, Borderlines, 2019. Image courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh.](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2019-04/1G7A1546-Edit.jpg?itok=SfyB1i1I)