Counterpoint

-

Ross Birrell, Keith Farquhar, Alec Finlay, Michelle Hannah, Ellie Harrison, Shona Macnaughton, Andrew Miller, Craig Mulholland

'Counterpoint,' part of Generation 2014 and Edinburgh Art Festival, sees Talbot Rice Gallery play host to a range of diverse installation works, including; two full size streetlights, a breakfast bar, and a custom-made bowling alley. The exhibition will lead audiences through a thought-provoking encounter with political and philosophical ideas, poetry and music, conceptual art and technological visions of the future.

Michelle Hannah and Shona Macnaughton each present work that engages with the institutional architecture of Talbot Rice Gallery and its Old College setting. In a political gesture Ellie Harrison’s project 'After The Revolution, Who Will Clean Up The Mess?' is a direct response to the upcoming vote on Scottish independence. Appropriating American artist Christopher Wool’s spray-paint gestures, Keith Farquhar mimics the work using contemporary print technology and large corrugated metal sheets. He also presents 'More Dream Material,' two public streetlights, illuminated and laid on their side along the length of the neoclassical gallery, creating an audacious presence in the historic room.

In the centre of the main gallery, Andrew Miller has constructed a ‘breakfast bar’ structure, which will act as a meeting point and a site for dialogue and creative exchange. Craig Mulholland presents 'POTEMKIN FUNKTION,' a complex and immersive installation including electronic sound, a mesmerising voice over and a custom-made bowling alley. Ross Birrell’s work adds another political dimension to Counterpoint, also referencing the vote on September 18. On this date Birrell will throw a metal cast of Werner Heisenberg’s equation for the ‘uncertainty relation of waves’ into the Firth of Clyde. And in the upper gallery, Alec Finlay’s 'Global Oracle' is a poetic multimedia work that compares satellite communication, GPS navigation and the innate spatial memory of bees.

Realised in collaboration with National Galleries Scotland, Glasgow Life, Creative Scotland, Event Scotland and British Council Scotland.

Exhibition Guide

Published on the occasion of 'Counterpoint' at Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh.

Texts are available to view below or download.

'Counterpoint' showcases new commissioned work by eight contemporary artists who question the social role and function of art. As a non-thematic exhibition, the artists’ enquiries into the contemporary world present distinct voices that cross, divide or collude in philosophical refrains, poetry, science fiction and the aesthetics of everyday life. The installations, including confetti cannons, a bowling alley and full-size street lamps, allude to performance and participation, and invite an active political engagement with debates about technology, utopia and the Scottish Referendum.

The active aspect of 'Counterpoint' is extended by a programme of events including performances by Jeans & MacDonald, Ortonandon and Alexa Hare (see reverse for full details). As part of GENERATION and Edinburgh Art Festival, Counterpoint is a generative survey of artists emerging at different points during the last 25 years and a celebration of the transformative and re-interpretative nature of creative practice.

The work of Michelle Hannah, Ellie Harrison, Shona Macnaughton and the Counterpoint Performance artists has been co-commissioned with Edinburgh Art Festival, supported through the Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo fund.

GENERATION is delivered as a partnership between the National Galleries of Scotland, Glasgow Life and Creative Scotland and is part of Culture 2014, the Glasgow 2014 Cultural Programme. The programme traces the developments of art in Scotland since 1989. It shows the generation of ideas, of experiences, and of world-class art on an unparalleled scale by over 100 artists in more than 60 venues. The artists within GENERATION came to attention whilst working in Scotland, helping to create the vibrant and internationally recognised contemporary art scene that exists here today.

The eight artists were all asked questions that would reflect upon their broader practices, draw out important themes and provide an introduction to their work for 'Counterpoint.'

Michelle Hannah

Do you relate to a 20th century history of performance art or are your performances related to a whole other genre: theatre or the original Dada Cabaret Voltaire, for example?

I think I relate to both. There are elements of the history of 'performance art' in my process, as in the paint on my hands, improvisation and the ephemeral nature of the filming. I don't plan and react to the space I perform in. But I was thinking recently of the influences of pop culture, not necessarily pop art, on me: i.e. the performative and mythologising aspects of the pop video/pop star. Grace Jones, Kraftwerk Annie Lennox..it’s performance art too. Remember, I'm of the MTV generation... in between analogue and digital. Pre- and Post- Internet. I'm creating a science fiction self. The work in Counterpoint is greatly influenced by the book Vermillion Sands by JG Ballard*. I imagine being in this futurist utopia; in the Playfair Library lamenting as a dystopian chanteuse with a crystal face and singing to the blind statues.

The Plastic Palace People.

*A collection of short stories about a fully automated desert-resort. In severe decline, Vermillion Sands is home to forgotten movie stars and disaffected celebrities who are driven by malignant obsessions.

Andrew Miller

Would you identify with the description that you are a creator of spatial zones for activity to happen?

Over the past twenty years I have made various works which have encouraged the viewer to engage with both the work and the space it occupies, from walkway ramps to various library works. The Waiting Place (2012) was a wooden pavilion structure that was sited in Hanover square for Edinburgh Art Festival. This was a temporary space which enabled the public to interact with the building for many different reasons: for readings, performances, talks or simply sheltering from the rain.

For Counterpoint I am revisiting a work called Breakfast Bar (1995). It consisted of a painted steel barrier and two wooden structures and you were able to interact with by either standing or sitting at it; you could make some coffee, flick a magazine – it was a space for encouraging conversation.

Refraction (2014) is a larger free standing version, using similar materials as before. I wanted to make a work that would have a playful and sculptural presence in the space, which would offer the possibility of interaction as much about looking out at the rest of the space as it is about looking in to the work.

I am fascinated with our relationship to objects and how we encounter them; my sculptural work is closely connected to the photographs I have made of discarded objects. Both types of work are made in recognition of the potential for accidental and improvised associations to materials and structures and I strive to foster curiosity in the discarded, worn and redundant, through appropriation and reframing.

Ross Birrell

Envoy seems to encapsulate many facets of your practice - how would you describe the inherent ideas in the work?

Envoy is a series of site-specific gestures performed across the globe. Early works were responses to a reading of utopian literature and research into rituals of gift-exchange and potlatch, resulting in works such as: A copy of Thomas More’s Utopia gifted to the International Court of Justice, the Hague (2000) and A copy of Thomas More’s Utopia gifted to the United Nations, New York (2000); reading Thoreau’s Walden in Lapland or Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward in Celebration, Florida; The Stars & Stripes thrown into the Hudson River, New York (2000).

These works were a response to the failure of utopian ‘grand narratives’ and to where this left the political or social role of the artist as conveyor of messages and producer of meanings. The ghost of this legacy appears perhaps in the figure of the artist as an ‘envoy’ sent by an unknown power for an unspecified end. The envoy has no subjectivity (and is not always me); rather it’s an ‘agency’, an ‘it’. It gifts, it reads, it throws. Envoy remains structured around these gestures of gifting, reading or throwing encountered in the gallery as photographs, videos and wall texts.

Although less visibly engaged with the legacy of utopianism, the duality of gifting and throwing still permeates more recent Envoy works, such as Being & Time (2012), in which a copy of Heidegger’s Being & Time is thrown into the Grand Canyon, and A Dice Throw (2014), the new Envoy work made specifically for Counterpoint in which Heisenberg’s Uncertainty principle is cast into the Firth of Clyde.

Heidegger published Being & Time in 1927, the same year that Heisenberg published his paper on Uncertainty relations in which he demonstrates the indeterminacy of observations in quantum physics. There are parallels between Heidegger’s concept of ‘being-in-the-world’ and Heisenberg’s observation of an ‘electron-with-a-position’; the two figures knew and respected each other, and even died in the same year (1976). On a more sinister note, both men had a controversial relationship to the Nazis, Heidegger becoming Rector of Freiberg University in 1933 and Heisenberg being tasked with developing the atom bomb for the Germans in WWII – which he failed to do. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle became influential in later quantum physicists’ claims for the existence of parallel universes. So, Heisenberg’s equation will be cast in copper (in homage to potlatch), and thrown into the Firth of Clyde, the home of Trident nuclear submarine, on the day of the Scottish Independence referendum. On this day, the parallel universes of United Kingdom and Independent Scotland will co-exist.

The title and layout of the painted wall text is borrowed from Mallarme’s poem, A Dice Throw. Casting a vote is another form of a game of chance, and either way the future of Scotland remains uncertain. Even the words ‘UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE’ are difficult to discern, painted green against blue. As Wittgenstein says in Remarks on Colour: ‘In any serious question uncertainty extends to the very roots of the problem.’

Parallel to the Envoy works have been a series of works related to the hand, including a series of casts of a musician’s hand and of the Italian philosopher Paolo Virno (2011/14). The most recent work in this series is Conrad’s Hand, an X-Ray of the hand of Joseph Conrad taken on the occasion of a visit by Conrad in 1898 to the Glasgow flat of the renowned radiologist Dr. John MacIntyre. The X-Ray will be shown in the Anatomy Museum, Edinburgh, alongside a letter by Conrad which relates a drunken conversation with MacIntyre on the potential existence of ‘an infinity of different universes’.

Craig Mulholland

Is there a hierarchy in the complex facets of your work – performance / audio / visual display / publication / recordings?

Lately any hierarchies are beginning to dissolve, as a result of attempting to set up a dialectic between the concrete and virtual components of my work. There appears to be a drift towards transliminal and dematerialised territories with regards to media, perhaps as a result of a shifting perspective generated by previous work.

Earlier pieces tried to embody the steady colonisation of our concrete world by the digital, from a materialist position, tracing its effects and consequences on the corporeal, identity and social/labour relations. At this point hierarchies between media were much more pronounced, as an attempt to interrogate and exorcise any Luddite and essentialist sympa- thies I inherited from more orthodox Marxist critique. Through empirical means I discovered an underlying absurdity in the logic of materialism and have since sought to embrace more trans modes of production guided by aspects of queer theory. Most recently, the formerly discrete differences between media or facets, have begun to generate new points of synthesis for my work and hopefully a more radical post-human engagement with ontology.

Alec Finlay

Would it be appropriate to describe your work as a defence of nature?

I recently read a phrase from Michael Hamburger: “The poet can renovate the wilderness”. Can any of us really hope to do that? Perhaps, by bestowing a non-possessive claim, in the same way that walkers reveal the contested state of a landscape by their footfall. A mountain doesn’t know its name; walkers are sometimes vague about the memory of a place. Bees have no awareness of artworks, or poems, though they may choose to dwell in one of the book-nests I fabricate for them. My work gestures towards their residence in our world. Their ancient oracular status is presci- ent, for the downfall of the bees is our future. But these idioms are cultural, not biological – language is the ground for the work, not cells, or genes.

The question remains: what defends nature? I believe that names, alignments, small-scale dwellings – huts for humans, hives for bees – are civilizing alternatives to power and riches; I experience them as de-celeratory, and it is speed – the velocity of greed – that is the issue today. Art, poems, they are ways to love things, while also admitting their complexity, their reality, which is to say, also, their poetics. Of course, loss is a familiar of poetry, and that is its own truth. Toxic neonicotinoids are complex, lacking in poetry, and in the bees terms, there is no defence unless we “renovate” ourselves.

Shona Macnaughton

How does your creative process begin? In the case of Counterpoint we have the complication of film, of objects and importantly the script; is the script the trigger?

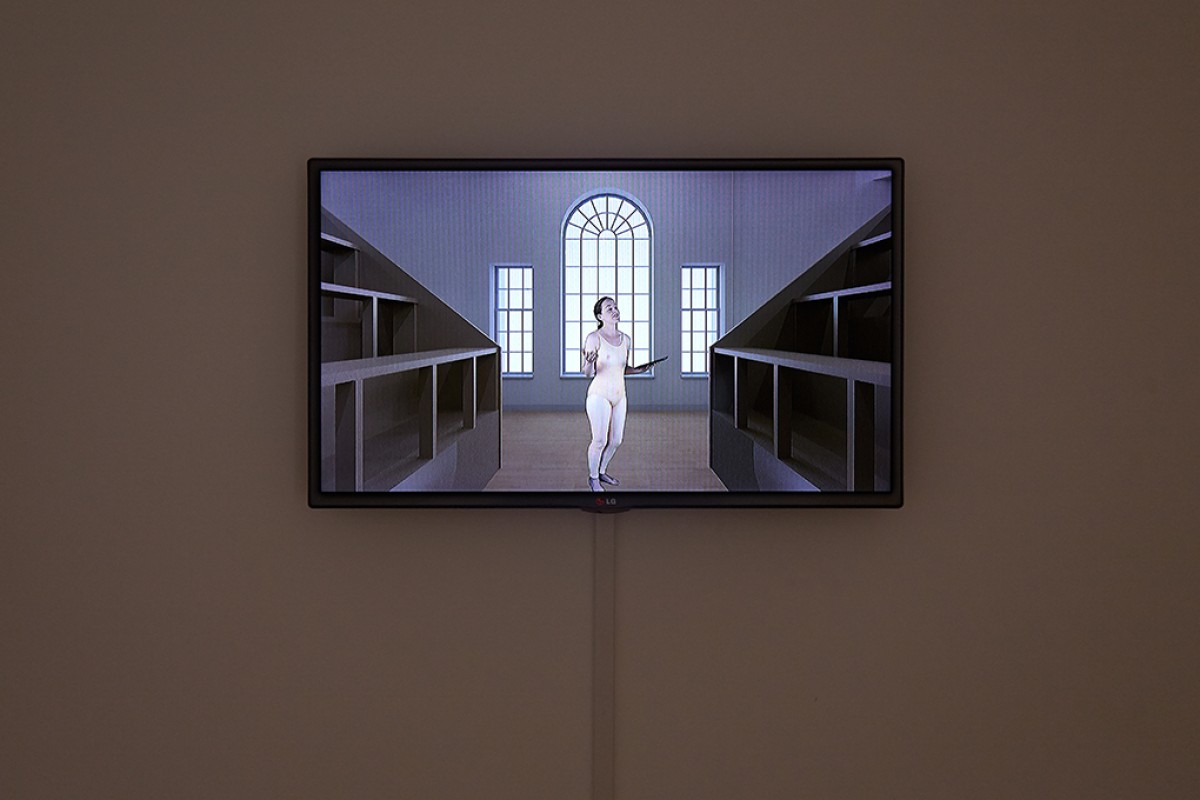

It is a very textual process, it all centres on writing. In Counterpoint I am directly adapting the existing play The Maids by Jean Genet and writing around that. I am interested in the aesthetic architecture of something and what it might represent, in this case the University of Edinburgh and its place in the construction of a humanist and capitalistic framework. I have commissioned a 3D model of the Talbot Rice Gallery, reverting to the architecture of the Natural Philosophy classroom as it was planned at the end of the 18th century, but retaining the interior feel of the modern day gallery. A model is propositional by its very nature, so this is intended to speculate upon what an institution founded on the post-human would look like, in the very place that could be said to symbolise the primacy of the human.

The Maids is a classic tale of class dynamics and it follows quite nicely from my previous work where I have used my own working conditions as a material for a kind of structural- ist video approach to directly represent workplaces. During the process of building the model I also discovered the website Turbos- quid where 3D models of women are sold, alongside furniture and other 3D objects, which followed a very specific aesthetic pattern and seemed to sit so much on the border between reality and fiction that it tapped into an odd ethical or moralistic discomfort. The women can look almost real are priced according to their authenticity. They are a new kind of slave, where I become the master. I have taken this rather literally. I become the Madame character from The Maids, ‘the maids’ become 'The 3D models' which become 'The Students'. It's a collage. I write from the images.

All the elements are intended to fit together as a narrative, to act as a way into the processes I describe. The first things you should encounter are the preamble, serving as an introduction to the aftermath depicted in the three screen video When slaves love one another. Conference Table is from a previous body of work, which used fragments of footage recorded whilst working for functions and events at Edinburgh University. Churned through the workplace and out again, it serves as a linkage from the supposed reality of the contemporary university and the virtual surreality of the landscape I have created.

Keith Farquhar

What kind of potential do you look for in the found materials and art historical ideas you appropriate to make your work? Is it complex?

Complex? I’m sure. Yet I don’t want the work to be over-rational. Having potential is a good attribute - I like the work to be pregnant with connotations as much as smart references - (Endless referencing becomes conspicuous consumption). The most successful cultural references are surely those coloured by subjective experience. This is the case with my using the Professor Higgs image on the cover of the Edinburgh University magazine. I’d recently begun teaching at the art college (which is part of Edinburgh University) and there were pictures of Higgs everywhere. These magazines were lying around the staff room. The image stayed with me. It seemed both historically significant and yet personal: It was in my pigeon-hole.

The lampposts (More Dream Material) were first exhibited in the sculpture court at Edinburgh College of Art in 1993 when I was a final year undergrad student. They were perhaps my first ‘mature’ work and can be read within the context of the readymade. I saw then the great economy the work has: the effortless anthropomorphism: By bringing the street-lights inside and lying them down alongside one-another a spectacle was produced that had a profound impact on many viewers. A memory I have is of these huge lights being wired-up by the college electrician with a 13 amp plug and plugged straight into the domestic socket. It was a fabulous and bizarre collision of scale.

Making art though is never merely about signs and signifiers - there is also the materialism of stuff to consider. My Christopher Wool Spray-paint appropriations are a good example of this (the work on corrugated steel). These works came into being in a round-about way through first reconsidering the technologi- cal possibilities of what was available to me at the time. I gained access to a large scale UV-direct printer and found that by raising its print-heads and allowing its inkjet to diffuse in space, I could manipulate it into producing what looked like spray-paint: I could trick the printer into behaving like a spray-gun. Only then did I look online for ‘photographic images of spray-paint’, to transform back into ‘real spray-paint’ through misusing the printing process in this way. This is how I came about finding and then utilising the Chris Wool images. Sort of referencing ‘in reverse’ or ‘by default’ if you like.

Ellie Harrison

Do art and culture have the power to elicit political change?

I don't think art has much power in eliciting political change. That is why I split my time between direct activism (mainly campaigning for the public ownership of our public transport system with Bring Back British Rail, which I founded in 2009), and creating frivolous artworld spectacles that simply draw attention to my areas of concern in playful and engaging ways.

This latter role provides an essential release from the soul destroying slog of trying to change the world for the better, and ameliorate all the damage caused by free-market capitalism. Artists, unlike politicians, are allowed to make fools of themselves, to be silly and fail. They can be ambiguous and pose questions rather than have all the solutions meticulously planned out. That's why I keep coming back to it!

After the Revolution, Who Will Clean Up the Mess? – my new installation / event for Counterpoint, expands on my interest in exploring the role of the artist as commentator on current affairs (as well as agent for social change). It is an artwork completely contingent on the result of the Referendum on Scottish Independence on 18 September 2014. The four large confetti cannons installed inside Talbot Rice Gallery’s ornate Georgian Gallery will only be detonated in the event of a YES vote. If a NO vote is declared, the cannons will remain dormant for the entire duration of the exhibition and we will never witness what might have been.

Just like the nation of Scotland at this historic crossroads, After the Revolution... has two distinct possible futures that could have dramatic impact on its surroundings. Creating its own aura of uncertainty, anticipation, excitement (and potential anti-climax) within the confines of the gallery space, the artwork aims to replicate the atmosphere being felt across society in the run up to the Referendum and to visualise the possibilities and conse- quences of radical political change.

The artwork takes its title from early feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Maintenance Art Manifesto (1969), who poses the question, “after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”, knowing that it will be the women. After the Revolution... is also inspired by conversations I have had with my mum about the mess that will be made by a YES vote, all the bureaucratic ‘decoupling’ between England and Scotland’s institutions, which could go on and on for years.

But ultimately After the Revolution... is an anti-art gesture exploring the artist’s relation- ship with and respect for the conventions of the gallery space. The installation creates a system which could result in the temporary destruction and defacement of the gallery and the artworks in it. However, responsibility over whether or not it is activated is put completely beyond my control. The will of the nation shall decide.