At the Gates

-

![Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment (Áine Phillips). 'Bannerettes R-E-P-E-A-L', 2017. Navine G. Khan-Dossos, 'Bulk Targets, 1-100' [detail], 2018. Installation view At the Gates, 2018. Courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh.](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2019-04/1G7A0166_0.jpg?itok=oIXLHAvs)

Maja Bajevic, Georgia Horgan, Navine G. Khan-Dossos, Teresa Margolles, Olivia Plender, Suzanne Treister, Artists' Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment

Inspired by the tidal wave of change that has been sweeping the world, At the Gates brings together artists whose voices have amplified the global struggle towards female self-empowerment, and in the case of Ireland’s historic fight against the Eighth Amendment, right to bodily self-determination.

Often brushing up against the law, or institutions of power, these artists and their individual projects attest to the volume that can amass as these voices, images, banners, objects and artworks become part of a public discussion.

Shown alongside Jesse Jones’ performance installation 'Tremble Tremble', the implication is clear: “tremble, tremble, the witches have returned”.

At the Gates is currently showing at La Criée centre d'art contemporain, Rennes, France from 15 June to 25 August 2019.

Share

Exhibition Guide

Published on the occasion of 'At the Gates' at Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh.

Texts by Tessa Giblin and James Clegg are available to view below, or download free of charge.

Navine G. Khan-Dossos

'Bulk Targets 1-100', 2018

The 90 paintings being shown by Navine G. Khan-Dossos are titled 'Bulk Targets 1-100' and were originally made for an exhibition that the artist called 'Shoot the Women First'. Their joyful, bauble-like decorative quality belies their original purpose, as the paintings are made on real shooting-range targets that the artist sourced in bulk from the U.S. Khan-Dossos has hand painted each card, mimicking geometric shapes that are used to indicate speci c parts of the target to be aimed for on command, designed to teach shooters how their rounds will affect the human body. Called ‘The IQ Target’, they were created to allow trainers to instruct their students: ‘shoot the yellows’, ‘shoot the squares’, or more complex instructions, ‘shoot the squares in order from light to dark but not if they overlap the white.’ These instructions connect for Khan-Dossos around what she had been reading about anti-terror squad approaches to female terrorists, to shoot the women first.

The pink shapes are an addition by the artist to the established shooting range code, and reference gay rights movements and AIDS activism, but also point to the local history of the Breeder Gallery in Athens, sitting in a neighbourhood where women were targeted and publicly stigmatised as bio-terrorists. Khan-Dossos writes as an introduction to 'Shoot the Women First', ‘The violence represented is not merely physical, but embodies a wider threat to society by those who exist on the periphery of mainstream politics and culture... Within the Greek context, they were shaped by the 2012 arrests of female drug-users suspected of doing casual sex work in Athens, the forced HIV testing of these women, and the imprisonment of those with a positive test result, accused of grievous bodily harm (GBH) by transmitting the virus.'

'The release of the suspects’ personal information by the police to the media led to further stigmatisation and terrorising of female sex workers and women living with HIV.’ Jasmina Tumbas writes in 'ASAP Journal', ‘Khan-Dossos’ feminist lens puts forth the argument that 'Shoot the Women First' is not just about the terror political women might pose for Interpol, but the terror of and for those women, who demand to be paid for their labour below the belt.’

When shown originally in Athens, Khan-Dossos created a performance with choreographer Yasmina Reggad, in which women who were wearing the targets on their backs moved around the gallery, their movement based on martial arts and formations used by riot police in con ict situations. She turned her female performers into targets and now forces us to confront those targets, either on the wall, bunched in stacks on the ground or worn on the back. She doesn’t focus the gun, doesn’t cock the trigger, but instead asks the viewer to do it in their mind’s eye.

Maja Bajevic

How Do You Want to Be Governed, 2009

To Be Continued – Archive, 2011

To Be Continued – Performance(s), 2011 – ongoing

Maja Bajevic contributes her enduring work 'How do you Want to Be Governed', alongside three manifestations of the ongoing series 'To Be Continued'. Made in the context of the last century’s political agitation, 'To Be Continued' will remain incomplete as long as the artist continues to work on it. However, Bajevic’s selection of slogans is diverse, ranging from familiar campaign friendly catch-words to more insidious messaging from dark moments of 20th century history. In each of the pages held in 'To Be Continued – Archive', Maja Bajevic and her collaborators have written descriptions of the slogans, contextualising their emergence and what they sought to describe. These pages are free to be rifled through, a growing archive of historical phraseology, harbouring various ideologies. Alongside are two performance works – a sound work in which the slogans are sung as tunes, carefully sequenced in such a way that their content seems to overlap to create a continuum, and a live performance on the opening night that remains throughout the exhibition. Staged as a work-scene, this piece sees performers methodically inscribe various slogans drawn from the archive into the mud-smeared windows of the Gallery, working as a team and climbing up and down the platform throughout the night. As they work, enacting the labour of a cleaning crew, the slogans they inscribe build up like a cacophony of histories, repeatedly washed o and re- written again as if a never-ending task. Out of context, without their reasoning, they are memories of the past, disassociated fragments of campaigns, but clearly framed, as Raphael Gygax writes ‘as a mass medium for the dissemination of politically motivated ideologies. As fragments of a collective memory, they illustrate mechanisms of power and how they infuence the formation of national or ideological identities.’ Left in the Gallery to dry on the windows, the eeting moment of their action becomes memorialised just as the slogans are memorialised through the monumentality of the charged, sung verses.

Upstairs in the White Gallery and overlooking the rest of Maja Bajevic’s works is 'How Do You Want to Be Governed'. This small, human-sized monitor holds one of the key works in the exhibition, depicting a woman being rst asked, but increasingly harassed with the question – ‘how do you want to be governed?’ The subject, Maja Bajevic, remains mute throughout the interrogation, passively resisting the increasingly aggressive interlocuter, whose voice we hear and whose arms we see reaching out to pinch, slap, grasp the artist’s face. Her strength, in the face of a question impossible to answer from a position of inequality, is pronounced. Bajevic made the work in 2009 after the 1976 artwork by Rasa Todosijevic, 'What is Art?', but today it is as much in conversation with the Bajevic of 10 years ago as it is Todosijevic 50 years ago. Resistance is a constant labour, and while the artist remains resolute and silent in 'How Do You Want to Be Governed', her slogans from across history and the political spectrum are sung aloud, and memorialised in scrawl in 'To Be Continued'.

Suzanne Treister

'Alchemy' 2007-2008

From the early 1990s Suzanne Treister started to explore how digital and new media technologies might enable the creation of ctional worlds by producing – for example – computer game stills, imaginary software packages and interactive narratives. Based in other realities, and sometimes on long-term characters or alter- egos, they enabled Treister to take an alternative approach to examining the interplay of knowledge, power and identity.

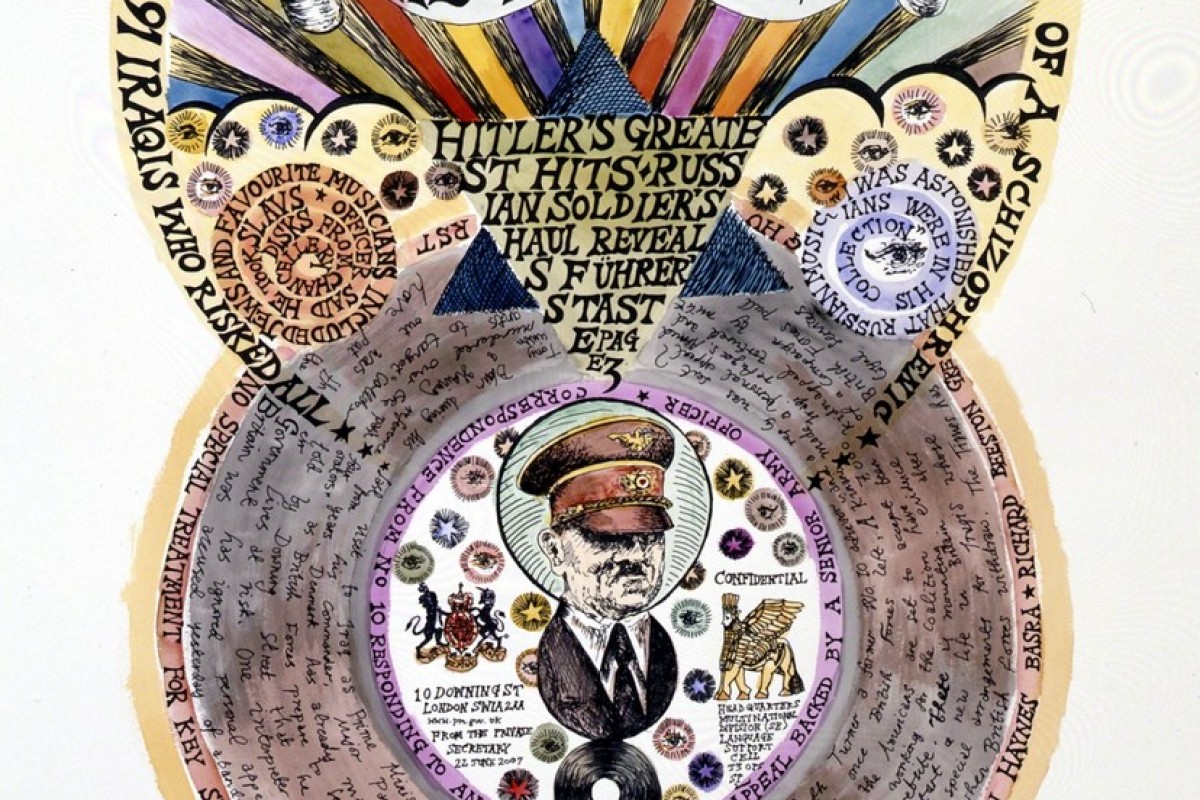

The ve works in 'At the Gates' plunge us back into the 2007 – 2008 period, showing us re and brimstone images of Gordon Brown’s rst day in o ce as soldiers die in Iraq; the creation of arti cial life amidst class war; in the States, Lewis Libby Jr. – a high ranking o cial in the George W. Bush administration – found guilty of interfering with a case investigating the leaked names of secret agents; questions of faith related to the inhabitants of the Gaza strip; foot and mouth disease; and Hitler’s Greatest Hits.

A crucible for different information types, ideologies and imagery, this melding of forms creates an ambivalent message that weaves together dark visions of terror with a kind of visceral, medieval euphoria. Similar in form to the tarot cards Treister has made previously, the works in 'Alchemy' act like runes: hidden symbols from which we must divine meaning. Yet it is unclear whether the explosive, crowded images are auspicious or ominous: signs of present day chaos or future revolutions. Removing journalistic conventions that usually suggest a degree of rationalisation, they certainly depict worlds animated by magic, superstition and the occult. In the context of 'At the Gates' we might consider them as upturning the normal world order represented by the media: a disturbance or disruption of ‘business as usual’. If alchemy once aimed at a perfection of the body and the soul, Alchemy suggests that – against our modern value systems – we must look again at the agitation and the energy of change, renewal and transmutation.

'Alchemy' also refects the complexity of Treister’s artistic position. Whilst known as a pioneer of new media art, she celebrates the ambition of pre-modern attempts to synthetize art, science and technology, as refected in the alchemical diagrams of the 16th and 17th centuries. And her engagement with technology has seen her return to traditional media, which she considers as a necessary move that allows her to retain criticality. In 2014 Treister (somewhat ironically) coined the term ‘post-surveillance art’ to, ‘...somehow describe a state where we are constantly uploading our lives and are complicit with government/corporate data collection, with sharing everything including our sex lives and our dreams, where algorithms are owing through our bodies and our appliances up to satellites in outer space and back, collecting data to be used wherever, whenever and by whoever... to perhaps describe a sublime poetics of control.’ Such sublime visions of control haunt 'Alchemy' too. In the media swarm we see the stirring of a freak otherness in which politics, identity and world events are being put to some other unearthly use. (JC)

Artists' Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment

'Dragonslayer', 2017

'Madonna of the Eyes', 2017

'The Journey Banner', 2017

'Respect', 2018

'Six of Swords', 2018

'Our Toil Doth Sweeten Others, 2017 Bannerettes: R-E-P-E-A-L', 2017

Motivated by the Catholic Church, the Eighth Amendment was an addition made to the Irish constitution in 1983 that equated the life of a pregnant woman with that of an unborn child. It had dire consequences for many women because it prohibited abortion, even when there was a risk to a woman’s health, the pregnancy stemmed from rape, or fatal foetal abnormality.

Set-up in 2015 by Cecily Brennan, Alice Maher, Eithne Jordan and Paula Meehan to find positive ways to raise awareness and bring people together to fight for women’s rights to bodily autonomy, the Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment quickly won the support of thousands of artists. Wanting to utilise existing skills, banners were adopted as a vehicle for the campaign, connecting the project to histories of protest and community driven activism. The banners in 'At the Gates' were made by Sarah Cullen, Rachel Fallon, Alice Maher, Breda Mayock and Áine Phillips. Their designs reflect a desire to remake familiar narratives in a way that empowers women and subverts the familiar religious and state enforced patriarchal order. 'Dragonslayer' is based on Orazio Gentileschi’s work 'David and Goliath', replacing David with a leather-jacket-wearing woman who slays the Eighth Amendment Dragon with her sword. It shifts the usual hierarchy in art history that depicts (often naked) women as vulnerable and passive. In 'Madonna of the Eyes', the Virgin Mary becomes an active prophet-like gure, opening out her cloak to reveal a commitment to repeal.

The eyes that adorn the cape represent the protection of an all-seeing community, continued through the Bannerettes. Remaking the silk scarf Grayson Perry made for the Tate – offering a navigation system for a lost artist moving through the wilderness of modern art – 'The Journey Banner' conjures a dark vision of how a pregnant woman must navigate the perils of childbirth in Ireland, including the trauma of having to travel for abortion. The artists reviewed women’s magazines in order to be able to react against the messages of 19th and 20th century visual culture. 'Our Toil Doth Sweeten Others' is appropriated from a Beekeeping Association Manual. In place of the bee is a vulvic eye form, suggesting the wide-scale labour of women and its direct connection to the body. 'Six of Swords' references the spiritual world and is taken from the tarot card of that name. In many versions of this card, a boatman is depicted rowing a huddled, cloaked woman across a body of water. Here the woman propels herself with a repeal banner – heading towards bodily self-determination.

Many of these banners were at various marches throughout the campaign. When first shown in Limerick, these banners were taken on a peaceful procession through the city with dancers, performers dressed in Magdalene costumes, designed aprons and accompanied by a song written by Breda Mayock, 'This is How We Rise'. (‘We see you through our eyes, see these are our rights, we’ll see them through this time...’). They were then displayed alongside videos of actors recreating women’s testimonies, evidencing the damage caused to women’s lives by the Eighth Amendment and the systematic discrimination it effectively condoned. On 25 May 2018, the Irish people voted by 66.4% to repeal the Eighth Amendment, paving the way for new abortion laws that will improve women’s healthcare and provides a more hopeful future for equality. (JC)

Olivia Plender

'Urania', 2015

'Learning to Speak Sense', 2015

'To Our Friends', 2015

Olivia Plender’s practice is devoted to historical research about social movements of the past. Her sound installation 'Learning to Speak Sense' reflects the trauma and violence experienced by those trying to find their voice in the face of authority. This artwork evolved from Plender’s own unforeseen encounter with the powerlessness that comes with the loss of the voice. Plender said, ‘When I lost my ability to speak for a whole year, after an illness in 2013, it profoundly changed the way that I thought about that subject. Being literally voiceless, I felt vulnerable in public space and over the course of my treatment I was exposed to a lot of institutional settings, such as hospitals... Many of the words, phrases and sentences that I was given as exercises by the hospital [appeared] to me to have some kind of hidden political message. For example... “Many Maids Make Much Noise”, or another phrase that I had to repeat “Militant Miners Means More Money”, both seem to speak about the power of the collective voice to be heard, demand attention, to “make noise”. In the British context, any reference to “militant miners” immediately seems to indicate the miner’s strike of the 1980s...

I became convinced that there [was] an anonymous author working as a care worker within the hospital system, who distributes their clandestine messages through the voices of individuals who are learning to speak. I found this idea very poetic.’

'Urania' introduces various characters and images that Plender has drawn from the magazine Urania, a political journal founded in 1915 that continued to be distributed to networks of friends until 1940. Founded by Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, both involved in the votes-for-women movement, 'Urania' provided a platform and home for queer and gender non-conforming people who were active and involved in political, often feminist movements. Plender was struck by the global reach of the articles – with stories of people escaping the law by cross- dressing and gender changing plants – submitted from around the world. Compiled through newspaper clippings, 'Urania', at the beginning of the 20th century, was a precursor to today’s Wikipedia, compiling various perspectives on a single topic for redistribution through user input. As such, Plender’s poster series 'Urania' reflects a uniquely disparate set of images and personages, originally compiled within the magazine 'Urania' through group resource and friendship, and then selected by Plender. The quilted 'To Our Friends' sits on top of a recessed plinth, and with the helpful pair of white gloves, invites visitors to peer inside the warm layers to read the magazine Urania’s statement of intent, stitched onto the bloody red inside surface of the quilt: ‘There are no “men” or “women” in Urania.’

In commenting on the role that art plays in the face of politics, Olivia Plender reminds us that history is a malleable thing, and that she’s bringing to light marginalised positions. History shapes the future, and whilst art is not always directly political it plays a vital role in reimagining the past. In this case, Plender brings to light a wealth of forgotten micro-histories and lost details in defiance of the more simplistic views often propagated by those in power.

Teresa Margolles

'Nkijak b'ey Pa jun utz laj K'aslemal (Opening Paths to Social Justice)', 2012-2015

Nkijak d'ey Oa jun utz laj K'aslemal (Opening Paths to Social Justice)', 2015

The violence experienced by women is a consistent focus of Teresa Margolles’ artistic practice. In 'At the Gates', Margolles presents an embroidered shroud and a documentary video, showing the making of the work. Entitled 'Nkijak b’ey Pa jun utz laj K’aslemal (Opening Paths to Social Justice)', designs are embroidered onto fabric previously stained with blood from the body of a woman assassinated in Guatemala City. A potent, auratic material to begin with, Margolles asked people from di erent communities throughout the Americas to work back into these objects of trauma. In documentary lms we see that the groups of artisans – including the Kunas of Panama, the Taharamaras of Mexico, and the Mayans of Guatamala – show care and respect for the dead woman, and acknowledge her and her ongoing gift as they work, often asking her permission in various gestures or ceremonies. As one of the Guatemalan embroiderers states during the video shown at TRG, ‘the blood spread on this fabric could have been one of us... Her blood is going to help us all. She is giving us freedom. She is giving us the voice, the energy, and the strength to be able to report, so other sisters don’t have to go through what she lived through, what she suffered.’ These artisans describe their actions variously as ‘repairs’, ‘healing’ or ‘embellishments’, while Margolles herself refers to them as ‘microphones’ through which local participants could express their concerns. In this particular work, the Mayan women describe their images as being drawn from their surroundings and their love of the natural world: ‘You can see that the lake is surrounding us. We are surrounded by water, by the mountains, by nature. They are the ones who give us back happiness. Maybe you noticed that in the fabric we embroidered the moon. The moon is our Grandma. She is always watching over us, even when it is rainy or foggy. This fabric will speak on behalf of the sister who has her blood on it, and it will speak on behalf of all of us who need peace in this place.’ They discuss the global sisters who need their strength, the other regions of the world where violence towards women is still extreme.

Margolles’ desire to display the textiles on lightboxes was nuanced. She wanted them to be able to be touched, not to create an unbroachable distance between the embodied material and the viewer. She also wanted to reveal the many layers of ‘messaging’ within them, from the sharp, colourful lines of the embroidery, to the faded stains of blood. In her practice, Margolles wants us to undergo an experience, whether lling a room with bubbles that have been made from the water that washed bodies clean in a morgue, or laying a new oor of concrete mixed with the same morgue waters. Her classical museological display evokes the ethics and politics of display; it also creates a powerful aura. These hallowed textiles, now complex objects that encapsulate terror, trauma, healing, faith, love and community, are hovering

in their darkened room, pulsating in the white light from beneath and the soft light from above. Although the artist shies away from readings of relics, her presentation of the work recalls the sacred. A quality that is here enhanced by her collaborators, with the Mayan women, who made the version on display here, pouring their love of community, belief in healing, faith in nature and the moon, waters and the land into a fabric stained with one of humanity’s dark moments.

Georgia Horgan

'Costumes for 'The Whore's Rhetoric', 2018

‘Read then this Book to expose all the tricks, and all the finesses you can find therein; carry it in your pockets, as some do pictures of poor Animals rotten with the Venereal distemper, to make you detest those Monsters, who can destroy miserable man with a single embrace ...’ Pallavicino, F., The Whore’s Rhetorick, 1683

Georgia Horgan has worked with costume designer Johanna Samuelson to create costumes for two characters from 'The Whore’s Rhetorick', a 'political pornography' from 1683. This type of literature developed with Royalist propaganda during The English Civil War (1642 – 1651), the word pornography deriving from porne, meaning ‘prostitute’, and graphein, meaning ‘to write’. The character Madam Cresswell (represented by the more practical dress in olive, oyster and navy) was based on the real Elizabeth Cresswell, a famed sex-worker and brothel owner. Her power was such that she nanced Whig (republican, parliamentary) political campaigns and supplied sex workers to the Royal Court. It was one of the aims of 'The Whore’s Rhetorick' to show how corrupting Cresswell was. To this end the author invented the beautiful and virginal Dorothea (the more ostentatious dress in greys and cream), the daughter of a Royalist family that has hit upon hard times. In the story this idealised character is slowly led into prostitution by Cresswell, who seduces her in part by the promise of glamour and riches.

Seventeenth-century English society was fraught with anxieties, the patriarchal establishment terri ed of social mobility, foreign invasion and declining moral standards. The textile industry was bound-up with these phobias in many complex ways: dress was thought to evidence social standing and propriety; textile merchants and apprentices had fought for the republican cause during The Civil War; and during the subsequent Restoration of the monarchy textiles became central to strategies for economic expansion tying it to national identity and prosperity. For the state and emergent mercantile class, who pro ted from this industry, labour was the key to controlling and disciplining workers’ bodies, with women being valued for their ability to reproduce, sustain a home and their role within the family. In this charged context, sex workers were demonised on multiple fronts. Maintaining ownership of their own commodity, notionally capable of upward mobility, masters of masquerade and transgressors of monogamous, marital relations, they were seen as a real threat to society and all it stood for.

With the newly created dresses, displayed on contemporary shop mannequins, Horgan aims to be trans-historical, showing that women’s bodies have always been a battle ground upon which capitalism has been fought. Intended for a new film she is planning to make in 2019, the dresses are dirtied and made to look worn. Her bold, graphic textual interventions into these historical forms will leave indelible traces in the lm of the literature that has attempted to construct narratives around the body. On one hand the snippets are derived from 'The Whore’s Rhetorick', on the other hand from Melissa Mowry’s critical essay, 'Dressing Up and Dressing Down: Prostitution, Pornography, and the Seventeenth-Century'. For 'At the Gates' ̧ the empty forms – loaded and interrupted by the words – suggest the maelstrom of competing values into which a body must enter and by which it is ultimately inscribed. (JC)

Artwork commissioned by Talbot Rice Gallery.

Before the Law by Franz Kafka (translated by Ian Johnston)

Before the law sits a gatekeeper. To this gatekeeper comes a man from the country who asks to gain entry into the law. But the gatekeeper says that he cannot grant him entry at the moment. The man thinks about it and then asks if he will be allowed to come in sometime later on. “It is possible,” says the gatekeeper, “but not now.” The gate to the law stands open, as always, and the gatekeeper walks to the side, so the man bends over in order to see through the gate into the inside. When the gatekeeper notices that, he laughs and says: “If it tempts you so much, try going inside in spite of my prohibition. But take note. I am powerful. And I am only the lowliest gatekeeper. But from room to room stand gatekeepers, each more powerful than the last. I cannot endure even one glimpse of the third.”

The man from the country has not expected such diffculties: the law should always be accessible for everyone, he thinks, but as he now looks more closely at the gatekeeper in his fur coat, at his large pointed nose and his long, thin, black Tartar’s beard, he decides that it would be better to wait until he gets permission to go inside. The gatekeeper gives him a stool and allows him to sit down at the side in front of the gate. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be let in, and he wears the gatekeeper out with his requests. The gatekeeper often interrogates him briefly, questioning him about his homeland and many other things, but they are indifferent questions, the kind great men put, and at the end he always tells him once more that he cannot let him inside yet.

The man, who has equipped himself with many things for his journey, spends everything, no matter how valuable, to win over the gatekeeper. The latter takes it all but, as he does so, says, “I am taking this only so that you do not think you have failed to do anything.” During the many years the man observes the gatekeeper almost continuously.

He forgets the other gatekeepers, and this one seems to him the only obstacle for entry into the law. He curses the unlucky circumstance, in the first years thoughtlessly and out loud; later, as he grows old, he only mumbles to himself. He becomes childish and, since in the long years studying the gatekeeper he has also come to know the fleas in his fur collar, he even asks the fleas to help him persuade the gatekeeper.

Finally his eyesight grows weak, and he does not know whether things are really darker around him or whether his eyes are merely deceiving him. But he recognizes now in the darkness an illumination which breaks inextinguishably out of the gateway to the law. Now he no longer has much time to live. Before his death he gathers up in his head all his experiences of the entire time into one question which he has not yet put to the gatekeeper. He waves to him, since he can no longer lift up his sti ening body. The gatekeeper has to bend way down to him, for the difference between them has changed considerably to the disadvantage of the man. “What do you want to know now?” asks the gatekeeper. “You are insatiable.” “Everyone strives after the law,” says the man, “so how is it that in these many years no one except me has requested entry?”

The gatekeeper sees that the man is already dying and, in order to reach his diminishing sense of hearing, he shouts at him, “Here no one else can gain entry, since this entrance was assigned only to you. I’m going now to close it.”

![Olivia Plender, 'Urania,' [detail], 2015. Installation view, At the Gates, 2018. Image courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2019-04/1G7A0337%20small_0.jpg?itok=c6k_kVNU)

![Teresa Margolles, 'Nkijak b’ey Pa jun utz laj K’aslemal (Opening Paths to Social Justice)', 2012-2015, [detail]. Installation view, At the Gates, 2018. Image courtesy Talbot Rice Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2019-04/1G7A0545.jpg?itok=L-Amwl0B)