Hanne Darboven / accepting anything among everything

-

The first major exhibition in Scotland of Hanne Darboven (1941 – 2009) offers a profound insight into the scale of human endeavour and comprehension. Showcasing the work of one of the last century’s most important conceptual artists, Talbot Rice Gallery will be covered by hundreds of framed objects, creating a spectacular monument to an extraordinary individual.

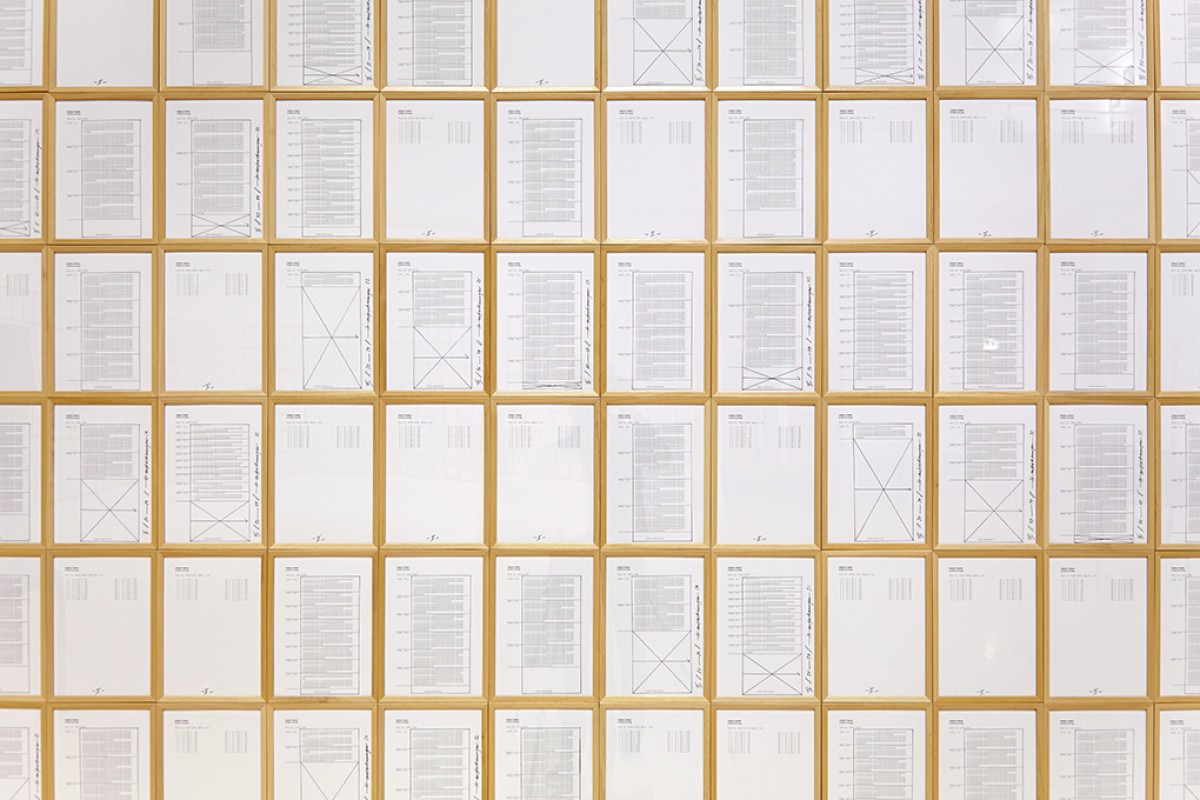

Becoming part of a generation of artists who challenged the way that art was understood and produced, Darboven went to New York to “find something I could work on for my whole life,” encapsulating the commitment she would make to a singular process. Based in Hamburg from 1968 onwards she became a ‘worker’ fulfilling a self-imposed duty to complete a predetermined series of actions day after day. Generating hundreds and even thousands of individual sheets for each work her simple processes extend rational systems of ordering information to the point where their meaning breaks down, giving way to what some have described as a ‘surplus of the real’.

Darboven’s work occupies a unique position within art history, somehow managing to be at once impersonal and devastatingly revealing. Working across vastly different scales, 'accepting anything among everything' opens out onto the overwhelming and endless progression of time and knowledge, whilst marking an individual’s action within it.

Realised in collaboration with the Hanne Darboven Foundation, Hamburg, and Sprüth Magers, Berlin and London. Supported by Creative Scotland, Goethe-Institut, Glasgow, and the Henry Moore Foundation.

Exhibition Guide

Published on the occasion of 'Hanne Darboven / accepting anything among everything' at Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh.

Texts by Miriam Schoofs are available to view below or download.

Hanne Darboven / accepting anything among everything

One of the most intriguing artists of the last century, Hanne Darboven (1941–2009) created a vast body of idiosyncratic works documenting her own systematic way of dealing with the weight of world history and culture. The first major exhibition in Scotland of her work, 'accepting anything among everything' is an unmissable mediation on the incalculability of experience.

In Gallery 1 is 'Life, living 1997-1998' (1998), an installation of 754 framed works ‘reckoning’ the years from 1900 to 1999 and Darboven’s experimental film, 'Four seasons. The moon has risen, opus 7, act I + II' (1982–83). Upstairs, the work 'Co-workers and friends' (1990) is accompanied by Walter Smerling’s documentary film 'Hanne Darboven, My secret is that I have none.'

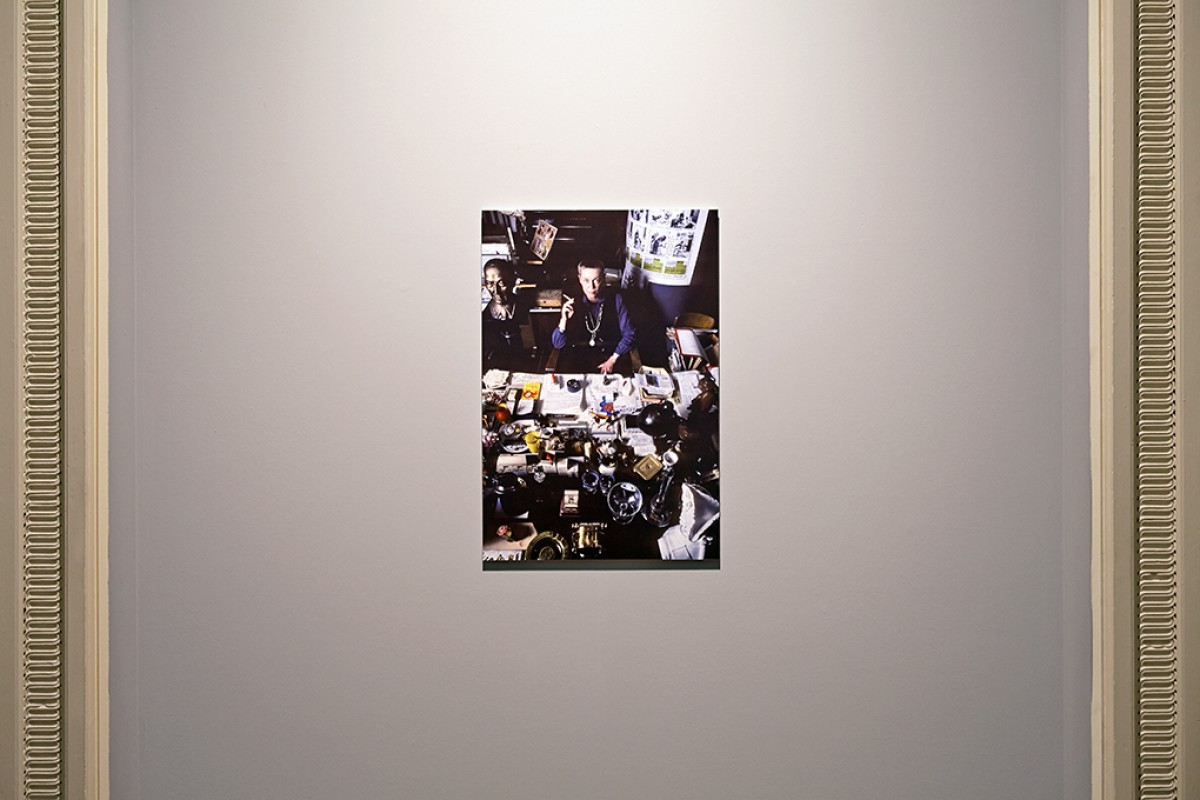

Gallery 2 centres upon an island of objects from Darboven’s home studio, reflecting the extensive encyclopaedic ‘nucleus’ of her work. Two photographic portraits by Hermann Dornhege complement the exhibition, along with a new essay by writer and curator Miriam Schoofs, contained within this guide.

The exhibition has been realised in collaboration with the Hanne Darboven Foundation, Hamburg, and Sprüth Magers, Berlin and London. Supported by Creative Scotland, Goethe-Institut, Glasgow, and the Henry Moore Foundation.

The Large Studio

Hanne Darboven’s Material World as “Work in Progress”

Miriam Schoofs

The family home and studio “Am Burgberg” in Hamburg-Harburg plays an important role in the life and work of the German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven. It was here that she lived until her untimely death in February 2009, leaving the seclusion of the family seat only for a two-year stay in New York during the mid-1960s. The gradual transformation of the buildings into a large studio complex is described within her serial writings in numerous notes and drawings, in her extensive correspondence and in her mother’s family albums, which testify at the same time to Darboven’s close ties to her parents’ home and to her origins.

The house is filled to the rafters with an extensive collection of art and artifacts, crafts, souvenirs, trinkets and curios from around the world, including the artist’s own works as well as gifts from other artists. In this it resembles more a cabinet of curiosities rather than a classic artist’s studio. Walter Smerling compares the interior of the studio building to “an extraordinary Museum of Modern History covering the last two hundred years” and describes the Darboven cosmos as a “different world”, which requires a new way of seeing and experiencing.

In the words of Klaus Honnef, the exhibition installations of her works, which are increasingly complemented by three-dimensional objects, are a “panoramic sensuously experienced world-incarnation” and he attributes to Darboven a quest for a “total work of art”. Elke Bippus compares the exhibition of 'Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983, 1980–1983)' to a “room-filling smorgasbord” and an “archive” in which the great narratives of modern cultural history are preserved: “The polarity between town and country, between public and private, photography and the Hollywood film.”

Darboven gradually moved from one room to the next, filling each with the innumerable items from her collection. Once all the rooms of the house had been filled, transforming former living areas into studio areas, she added more space through renovations and the addition of new buildings. Each room and each desk is now evidence of a particular phase in the life of the artist, and most are linked to the respective stages of her work and their particular subject areas. These are expressed through related props and motifs in the form of visual materials and collected objects on work tables, forming thematic ensembles. The themes of her work can be dated like archaeological layers, each representing an era of artistic inspiration, with each ensemble appearing as one of many possible choreographies of objects throughout the house. In Darboven’s system everything has its own meaningful space, in the relationships she has established and the scenarios she has presented. The visitors who squeeze through the narrow passages in this orchestrated world are asked to form their own pathways and associations. This is also the case in the large exhibition sections of Darboven’s work, some of them supplemented with objects chosen from the studio house, where it is up to the viewer to grasp the significance of the relationship between the paper works covering the walls and the sculptures and everyday objects accompanying the three-dimensional displays.

Except for the occasional removal or addition of individual objects, the cluttered studio spaces themselves resemble a “museum”, as Darboven herself sometimes called it, or else, “my collection”.

The accumulated objects can be roughly divided into those bought or commissioned under particular themes, those related closely with the origins and history of the Darboven family, and finally those in the form of gifts and souvenirs, often brought by fellow artists and friends and gradually integrated into the ensemble in the house. The shop furniture, billboards and coffee cans, for example, are reminders of the family’s coffee business. Last but not least, the many souvenirs mirror the cosmopolitanism of Darboven’s upper-class background, with the commercial and open-minded mentality of her Hanseatic father and the hospitality of her Danish mother. Overall, the objects create a complex synthesis of contemporary history with the artist’s own biography.

At the same time, the collection in the studio building served as a source of material for the artist’s works. Thus, for example, Darboven used photographs of individual objects as a leitmotif or integrated whole series of photographs as in the case of 'Bilddokumentation ›79‹ (Picture Documentation ›79‹' (1979) for the work entitled 'Bismarckzeit (Bismarck Era, 1979),' which portrays selected objects from her studio house in the form of an illustrated encyclopedia of technical, intellectual and historical symbols of modernity since the Enlightenment. She placed individual objects with certain works in an exhibition context together with framed works on paper. Beginning initially with sculpture and busts, she incorporated everyday objects, crafts and, increasingly, elements of pop culture from her collection into her exhibition presentations. Hanne Darboven’s passion for collecting and her artistic work are therefore not unconnected to one another. As a collector, she was always concerned with the environment of her work, and the objects of her collections embody a sense of the leitmotifs of her artistic work: writing and arithmetic, scientific and intellectual progress, technological development, history, colonialism, trade and time.

Darboven’s largest worktable is in the so-called “large studio”, a spacious, light-flooded room with skylights, extended into the space of the former stables in 1975. Here, for many years, Darboven received her guests in a small kitchenette, which was separated from the sprawling and cluttered table by a life-sized wooden horse that she had commissioned from the carpenter Hans-Heinrich Reese.

The tabletop is cluttered with all sorts of objects: a Tiffany lamp, small sculptures, busts and figurines, stuffed birds, vases and jewellery dishes, dried flowers in little baskets, candlesticks, the obligatory ashtrays and various writing utensils. On one side of the table a floor lamp rises in the form of a cobra. In the artist’s armchair, in her place, sits a doll in a child seat. Opposite this, a wooden figure of a golfer has been installed. The chair at the head of the table is enthroned by the figure of a witch, while the foot of the table is decorated with a metal bust of the “King of Rock ’n’ Roll”, Elvis Presley. The arrangement of antique objects, gems and everyday objects populated with such diverse characters, and the staged nature of the collections, bring to mind classical still lifes as well as surrealist compositions. Darboven, however, follows her own principles – as she does in her characteristic works on paper. She brings together elements from different worlds of ideas, mixing the classical canon of knowledge with peripheral or private anecdotal issues and materials. She always assembles a multitude of voices that seem to effect a chaotic cacophony, but on closer inspection turn out to follow a complex ordered scheme with idiosyncratic laws – just like her calculations, her writing systems and her musical scores. Darboven herself spoke of her system as “mathematical prose” and “mathematical music”, by means of which she defended herself successfully against any kind of political usurpation: as opposed to words, figures always refer only to themselves, and are therefore “sovereign and independent”.

Equally remarkable are the many postcard-sized wooden picture frames that are scattered like a kaleidoscope on the big table, filled with personal notes and musical scores, but especially with postcards, as well as with family photos and pictures of artist friends such as Roy Colmer, Sol LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner, as well as group photos of her employees. 'Mitarbeiter und Freunde (Co-workers and Friends, 1990)' is even the title of a very personal work by Darboven, incorporating a series of photographs of the legendary family and company parties of the Darbovens, which gives a vivid impression of family life and testifies to the close connection of the artist with her employees and friends. On these occasions her mother, and later Hanne Darboven herself, regularly invited a Gypsy band to play for them. Rarely does one see the androgynous woman as relaxed and happy as in these pictures.

Photography and postcards are used by the artist as the classical media of “the age of technological reproducibility” according to Walter Benjamin; so are the greeting and trading cards Darboven often integrated into her works. They are applied to communication media, cultural techniques and forms of reproduction of the previous century, which Darboven often discussed along with arithmetic, writing and offset printing in her works. Perhaps the vast collection of postcards by Sol LeWitt, who was a passionate collector of artworks himself, provided an encouraging example, and Darboven was also very familiar with “Mail Art” and was a lively correspondent via mail herself.

Finally, the family seat “Am Burgberg” appears throughout her work as both text and image: in the form of personal comments, as a supplement to her signature or even replacing it – “HD, Am Burgberg” or “Am Burgberg”. By mounting postcards and photographs of the interior of her studio house, Darboven allowed a quasi virtual tour of the house, thus providing a glimpse into her personal living and working environment.

The alleged discrepancy between disciplined restriction on the one side and obsessive passion for collecting on the other, between conceptual sobriety and self-indulgence, between the avoidance of any emotion and an unabashed tendency to kitsch infused Hanne Darboven’s life and work. Darboven herself speaks of her oscillation between rational rigor and the expansive material world as “Maximal Art” – and defies any conventional categorization of her work. Like Marcel Duchamp’s 'Large Glass,' which the artist spent years creating, Hanne Darboven’s “Large Studio” was itself, like her continuous writing, a work in progress and a life-time project – a Gesamtkunstwerk “definitively unfinished.”

Miriam Schoofs is a curator and author based in Berlin and Hamburg. She was researcher of the Erika Hoffmann Collection in Berlin and curator of the Falckenberg Collection, Hamburg. Since 2013, as PhD candidate in art history, she has been researcher, curatorial consultant and writer for several Hanne Darboven presentations and exhibitions and is a member of the advisory board for the Hanne Darboven Foundation, Hamburg.