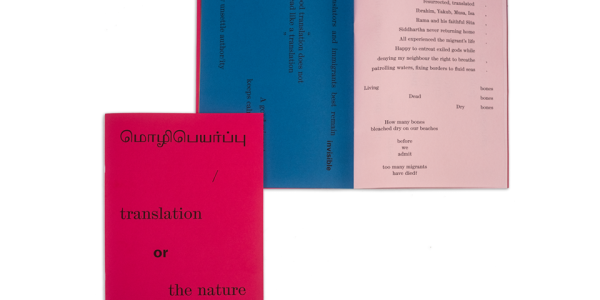

Hephzibah Israel / மொழிபெயர்ப்பு / the nature of difference

-

மொழிபெயர்ப்பு

/

translation

or

the nature

of difference

is a series of twenty individual text works by Hephzibah Israel, commissioned by Talbot Rice Gallery and produced in collaboration with Fraser Muggeridge studio. Israel’s script moves between Tamil, her native language, and Hindi and English, poetically exploring the nature of translation and what it is to navigate borders.

The Nature of Difference is informed by Israel’s own lived experience, which she describes as being on the margins of multiple communities. Born in southern India to a Tamil-speaking Christian household but growing up in the northern capital city of Delhi meant that she spoke multiple languages on a daily basis. Tamil was reserved for conversing with family in the home, Hindi on the streets, ‘Hinglish’ with friends, and English her language of formal education. Ironically, while she experienced a degree of racism in Delhi where ‘Madrasi’ (a pejorative term for a person from southern India) was a frequent term of abuse on the streets, her father insisted that Tamil was the ‘sweetest and best’ language in the world. Her Hebrew name has been the source of much confusion or amusement to those who first encounter her, as ‘Hephzibah’ does not fit neatly into cultural stereotypes or borders of race, religion or nationality. These early experiences of hybrid identities, of moving across visible and invisible borders, permeate her writing.

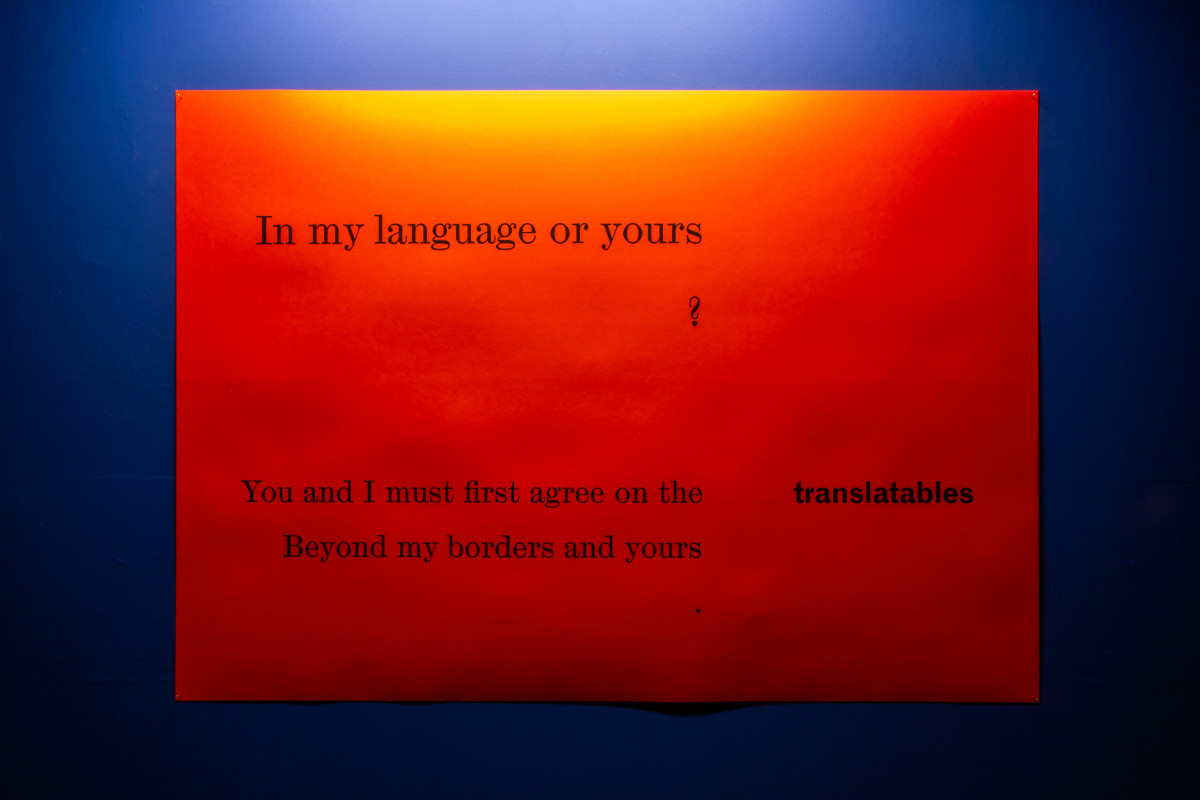

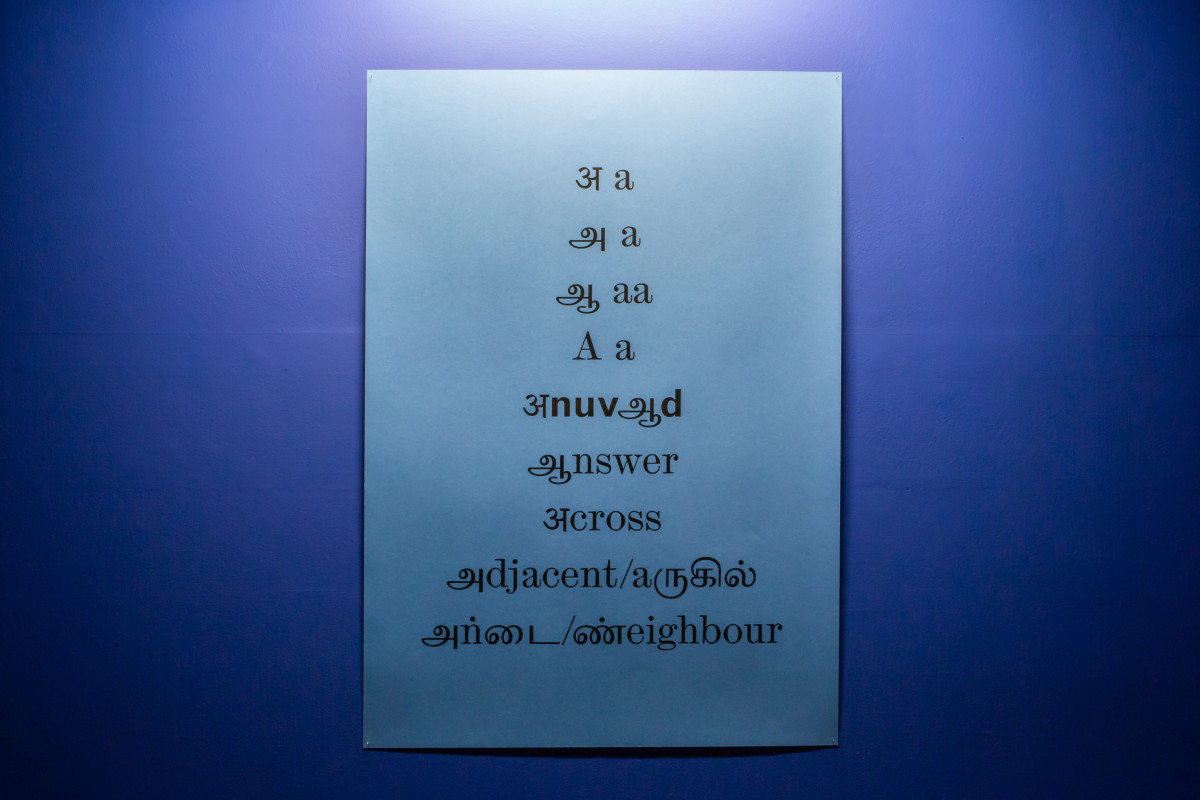

Through each text, presented as poster vignettes in individual bays of the Georgian Gallery balconies, Israel poses questions In your language or mine? and prompts us to consider our own perceptions of borders. Layering languages, she creates patterns - playfully employing the notion of translation as repetition. She delights in the ways the three languages and scripts relate to each other and to punctuation. Playing with punctuation offers space to think, invites us to insert further meanings, and is a reminder that its modern forms were introduced to Indian languages with European contact. At times, Israel deliberately does not translate the Tamil or Hindi script. As non-native Tamil, Hindi speakers, how does it feel when confronted by a statement that we do not understand when speaking of borders?

Israel is deeply interested in the translation of sacred texts. The original meaning of ‘translation’ comes from the Latin word ‘translatio’ which was first used in Medieval Europe to refer to the moving of the relics and bones of saints from one holy site to another. Throughout her texts, Israel makes direct reference to the Bible (she has studied the history of its translation into Tamil). Who is my neighbour? And Word made flesh. Ibrahim, Yakub, Musa, Isa – are Arabic for Abraham, Jacob, Moses and Jesus – reminding us of the shared roots of the three Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

As a resident in the UK for the past twenty years, Israel is the only member of her family with an Indian passport. Her poster vignettes evoke the emotional dilemma of where to call home - sharing tender moments of loss and grief, her Appa and Amma’s (father and mother) respective burials in India and the UK. ‘This other Eden, demi-paradise' is a direct quote from Richard II, one of Shakespeare’s most famous of lines that describes England as a kind of paradise. Just months before Amma’s death, Israel was travelling through Scotland with her, when Amma remarked that heaven would surely look like this. Israel reflects, “It is ironic when I think that I have lost her in and to this paradise – it changes my relationship to the country in an unanticipated way.”

Elsewhere, Israel alludes to Enoch Powell’s 1968 divisive “rivers of blood” speech against mass migration from Commonwealth countries, and reminds her, as a citizen of a former British colony, India, how dangerously close this comes to the political rhetoric of Westminster’s government today. Empire and imperial migration were acceptable to the British but not when migration flows in the opposite direction. ‘Not in my backyard’. She decries the buccaneering spirit of imperial nostalgia that fueled the Brexit campaign.

Her anger is palpable. What of the future of borders? Where empire builders erect militarised partitions and walls, implement surveillance drones, legislate draconian immigration policies, and deliberately withhold lifeboats to save those crossing the waves to seek refuge or a better life – furthering the inequalities of those who have and those who do not. Those on the ‘right’ side of the border from those on the ‘wrong’ side.

How many bones bleached dry on our beaches

before we admit

too many migrants have died?

Israel is haunted by the image of a young Syrian child’s body washed up on a Turkish beach after a failed attempt to reach Greece in 2015. In his 1987 publication Aliens and Citizens Joseph Carens issues a rallying call for open borders, questioning how it is justifiable that people die trying to cross borders because states deny access to their national territories. He writes, “Citizenship in Western liberal democracies is the modern equivalent of feudal privilege —an inherited status that greatly enhances one's life chances. Like feudal birth right privileges, restrictive citizenship is hard to justify when one thinks about it closely.”

Equal. Equivalent. “A good translator aims for equivalence between their translation and source texts. Another way of expressing equivalence is through the word ‘identical’, but the term ‘identity’ from which it derives has two opposite meanings: an exact copy and a unique factor, hence ID cards as unique signifiers of individuals.” (Hephzibah Israel). In practice, notions of equivalence between texts, languages or peoples are vexed – Some are more equal than others at border crossings. Israel encourages us to transgress and feel the weight of our civic responsibilities.

speak out,

re-translate,

intervene.

Even if we face no immediate harm.

Intervention is the refusal to remain silent

When they come for your neighbour.

She evokes the collective energy of a Glaswegian neighbourhood in 2021 who rejected a dawn raid seeking to forcibly remove asylum seekers from their homes during the holy Muslim celebration of Eid. Standing together in the street, members of the community, of all faiths, did not allow the Home Office van to pass.

And perhaps, most poignantly of all – in her texts, Israel reflects on our collective future to come. As we “hurtle towards a fatal point of no return” with rising sea levels, borderlines will dissolve as islands and coastlines disappear beneath the waves. Borders as we know them now may become irrelevant even as we scramble to police them harder.

Hephzibah Israel is Senior Lecturer in Translation Studies, University of Edinburgh. Her first and postgraduate degrees in English Literature were completed at the University of Delhi, India, where she also taught English literary studies for several years before moving to the UK. Hephzibah’s research explores the cultural history of South Asia through the lens of translation and language use in literary and religious contexts. She studies the encounters between writers and translators across religious traditions in colonial and contemporary South Asia. She loves translating as much as she enjoys teaching and talking about translation and its effects. She has authored Religious Transactions in Colonial South India: Language, Translation and the Making of Protestant Identity (2011) and has edited the Routledge Handbook of Translation and Religion (2023). She has collaborated on several research projects, from conversion accounts written and translated in colonial South Asia to the presence (and futures?) of colonial monuments in European and colonial public spaces.

Exhibition Guide