Pine's Eye

-

Firelei Báez, Beau Dick, Laurent Grasso, Alan Hunt, Torsten Lauschmann, Ana Mendieta, Kevin Mooney, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Taryn Simon, Johanna Unzueta, Lois Weinberger, Haegue Yang

Pine’s Eye explores what it means to be human in times of ecological change. Taking its name from 'Pinocchio' (the Italian for ‘pine eye’ or ‘kernel’) it is necessarily tricky and mischievous as it weaves a journey between subjectivities entangled in the natural world. Rejecting progress, purity, standardisation and originality it: creates new forms of ritual, reframes modernism as a pagan pursuit, asks flowers to bear witness to global treaties, observes the hybrid human and botanical cultures of enchanted islands, introduces inexplicable phenomenon into representations of early modern history, cultivates the weeds of European cities as a form of resistance, imagines alternatives to colonialism and introduces indigenous tales of the forest.

Through masks, mannequins and magic, Pine’s Eye offers alternative perspectives for how we understand ourselves in the face of environmental crisis. Including contemporary artists from both indigenous groups and the international artworld it features: Firelei Báez, Beau Dick, Laurent Grasso, Alan Hunt, Torsten Lauschmann, Ana Mendieta, Kevin Mooney, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Taryn Simon, Johanna Unzueta, Lois Weinberger, Haegue Yang

Dominican artist Firelei Báez makes work that critically engages with black female subjectivity, remaking art historical narratives by empowering regional mythologies. In 'I write love poems, too (The right to non-imperative clarities)' Báez mines pages of historic books that have been deemed irrelevant or inappropriate, to highlight and depict what or who is missing from the pages, whose stories are not told. Beau Dick (1955-2017) was a chief of the Kwakwaka’wakw of North West America who made carvings about the stories important to this culture’s cosmology. Hereditary Chief Alan Hunt and the Kwakwaka’wakw community will present 15 new masks that will be worn in a performance ceremony in Edinburgh, the first of its kind outside of Canada. Speck and Hunt’s masks represent the Atlakim story, the story of a boy who gets lost in the woods to be visited by many guiding spirits who teach him virtues. French artist Laurent Grasso is concerned with the relationship between art and science. 'Studies into the Past' establishes a false historical memory by inserting mysterious phenomenon into Renaissance-style images, disrupting our sense of this Euro-centric history and asking us to find a sense of wonder and strangeness in this hybrid, protomodern period of knowledge acquisition. Torsten Lauschmann uses different types and eras of technology to create mechanical and digital hybrids, automatons and sound machines. Ana Mendieta (1948- 1985), the legendary Cuban American artist, dedicated much of her career to exploring the “earth-body”. Delving into Mexican folklore, she used her own body as the site for staged ritual events that would unite her with the natural world. Her drawings derive from the performances and capture a sense of a timeless mother figure; seeds, kernels and eyes of humanity. Kevin Mooney is based in Cork and his intuitive paintings reinterpret Ireland’s colonial history and its stifled cultural heritage. Using layered imagery that incorporates straw, veiled figures and enigmatic forms, Mooney imagines how different this history could have been through collision with indigenous African and Caribbean cultures. Beatriz Santiago Muñoz makes documentary films that often centre on the ecology of her native Puerto Rico. The selection of films in Pine’s Eye explore how the hallucinogenic and toxic plants of this region have both expanded the mind and led to human tragedies, their role in magic and the changing everyday nature of the island as a result of tourism and adaptation. American artist Taryn Simon spent three years working with a botanist in order to be able to understand the composition of the flower arrangements appearing in photographs showing the signing of treaties, trade agreements and diplomatic accords. The large reconstructed bouquets in 'Paperwork and the Will of Capital' bear witness to changing global politics, whilst evoking Dutch still lifes and the impossible bouquet, where flowers that would not naturally bloom at the same time of year were painted into a single image. Johanna Unzueta is a Chilean artist who has dedicated much of her practice to understanding the tactility of industrial labour. Her drawings – which can take the form of large site-specific murals – evoke life cycles, play, plant life, weaving and intuition. Lois Weinberger lives and works in Austria. Seeing the garden as the antithesis of nature – orderly, designed, made on a human scale – Weinberger instead pursues an interest in ruderals – the ‘weeds’ that fight back against the logic of the city – and his practice revolves around inviting fungi into controlled spaces, designating ‘empty’ plots of land that develop their own ecologies, and displaying the organic debris of plants and animals growing in the recesses of our built environments. Haegue Yang presents an ensemble of sculptures from The Intermediates series on top of a nonagon shaped floor graphic with a new sound element synthesising her own voice, blending ideas of modernity, estrangement, pagan traditions and folk cultures to unsettle familiar hierarchies.

Atlakim Performance

In February 2020, for the first time, members of the Kwakwaka’wakw community performed the Atlakim ‘Dance of the Forest Spirits’ ceremony outside of Canada. Hereditary Chief Alan Hunt led the performance, helping to animate the legend that accompanies the 15 new masks he has made for the Pine’s Eye exhibition at Talbot Rice Gallery. Our thanks to Hereditary Chief William Hawkins, who has prerogative over the Atlakim as part of his Box of Treasures.

Including story-telling, music and dance, the performers assumed the role of forest spirits. In the Legend of Atlakim, these spirits visit Prince Kwak’wabalas in a sacred place and share with him a dance that will teach him respect for all living things.

Talbot Rice Gallery is grateful to the Kwakwaka’wakw community for sharing this ceremony. The event was made possible thanks to the kind support of Canada Council for the Arts and the High Commission of Canada in the United Kingdom.

Pine's Eye Profiles

Each week curator James Clegg takes a closer look at each

of the artists in Pine's Eye. The full series can be viewed here.

This week's profile is 'Forest spirits and resilience in the work of Alan Hunt'.

Exhibition Guide

Published on the occasion of 'Pine's Eye' at Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh, with texts by James Clegg, Curator. Texts are available to view below or download.

A large print guide is also available to download.

Children's Guide

Explore the magical world of Pine’s Eye with this resource designed especially for children, teachers and carers. From lumbering giants that might eat you, to the plants that go unnoticed, it offers lots of different ways for children to think about their relationship to nature. It includes twelve activities relating to the work of each artist that can be done at home, in the classroom or in the great outdoors.

Curator's Introduction | James Clegg, Curator at Talbot Rice Gallery

'Pine’s Eye' grew in response to calls for us to learn to think ecologically. With a sense that this would require a leap of the imagination and something very different from what passes as ‘logical thinking’, it derived its name from the meaning of the word Pinocchio. This madcap fairytale – with puppets as interesting metaphors for human-object relationships, anthropomorphic animals, spirits, enchanted woodlands and moralistic reflections on industry and greed – seemed to offer a suitably strange and magical point of departure.

Through the work of 12 international artists these ideas became entangled with global social and political concerns. Including stories from the Caribbean, the Americas and representatives of the Kwakwaka’wakw culture of the Pacific North West, it reflects the fact that the environmental crisis we face today is bound up with a longer history of colonialism: the repression of indigenous cultures, the loss of wisdom derived from animals and plants, and the industrial exploitation of people and resources. Working back and forwards across different time periods to reclaim indigenous, pagan, folk and ritual forms – and showing us nature in the most bureaucratic and urban situations – 'Pine’s Eye' questions the linear narrative of modernity, suggesting that its insistence on ruptures and breaks from the past are more about power than truth. Through its hauntings, ancestral connections and powerful mythical figures, it has become an exhibition about forms of resistance, resilience and different ways of being that should inform and inspire our ongoing relationship with nature.

Alan Hunt

'Atlakim Masks', 2019-2020

Hereditary Chief Alan Hunt is a Kwakwaka’wakw artist who has made 15 new masks for 'Pine’s Eye' that relate to the Atlakim or ‘Dance of the Forest Spirits’ ceremony, performed during the opening week of the exhibition.

These masks are always made from cedar wood, which is special to the Kwakwaka’wakw. They would typically be part of a potlatch ceremony taking place within the sacred space of the Big House in Alert Bay, Vancouver Island. Potlatch means ‘to gift’ and the ceremony is centred upon a Chief giving away their possessions to guests who, in return, listen to and acknowledge the truths that are being performed. These ceremonies are drawn from a Chief’s Box of Treasures, a box unique to that Chief’s prerogative and that includes specific songs, dances, stories and the regalia to perform them.

The attitudes of missionaries and government figures in the nineteenth century reflected an ignorance and contempt

for indigenous cultures, with many seeing the potlatch as ‘uncivilised’. In 1893, for example, John A. MacDonald the first Prime Minister of Canada proclaimed that the potlatch was, ‘the useless and degrading custom in vogue among the Indians ... at which an immense amount of personal property is squandered in gifts by one Band to another, and at which much valuable time is lost.’ Potlatch ceremonies were subsequently outlawed from 1885 to 1951, during which time practitioners were arrested and hundreds of objects were confiscated. Reflecting the broad remit of colonial projects to control indigenous cultures this was also a conflict between a system of capitalist accumulation and a Kwakwaka’wakw tradition that respects nature, celebrates giving and frowns upon greed. Famously, Chief Beau Dick – Hunt’s mentor – removed 40 masks from an exhibition in Vancouver and in front of the community, invited artists and curators, burnt them as part of a Potlatch. In so doing he aimed to emphasise that their importance lay in the ceremony and the ideas they could pass on - in remaking them as part of the cycle of nature – not in their status as commodities.

The Legend of Atlakim tells of Prince Kwak’wabalas who is so badly treated by his father that he heads into the forest to end his life. Surrounded by nature he has a change of heart. In some versions of the story a grouse caught in his snare promises to bestow upon him a gift if he lets him go. Following the grouse and eventually finding a lake, Kwak’wabalas is told in his dreams that he has arrived at a supernatural place. Here he is visited by the forest spirits who teach him valuable lessons, lessons he is told he will be able to later share with his community through dance. Led into the Atlakim dancehall he witnesses a life-changing ceremony. In original versions it included up to 40 characters, and here includes: Grouse, Spruce, Raindrop Maker, One Side Moss Face, Listener, Hamatsa, Door, Woman Giving Birth, Child, Infant, Midwife, Long Life Giver. They are characters connected to nature, the cycles of life and the condition of human appetite, who collectively show that everything in the natural world has a purpose. For the Kwakwaka’wakw, animals and plants are also people.

Beau Dick said that the teaching encompassed by a potlatch ceremony could include almost every aspect of life including ‘governance, medicine, justice, well-being, history, child rearing [and] honouring the dead.’ Whilst impossible to translate the complexities of the Atlakim ceremony, choosing to show the masks in other contexts, Hunt – like Dick – wants to share a respect for all living things.

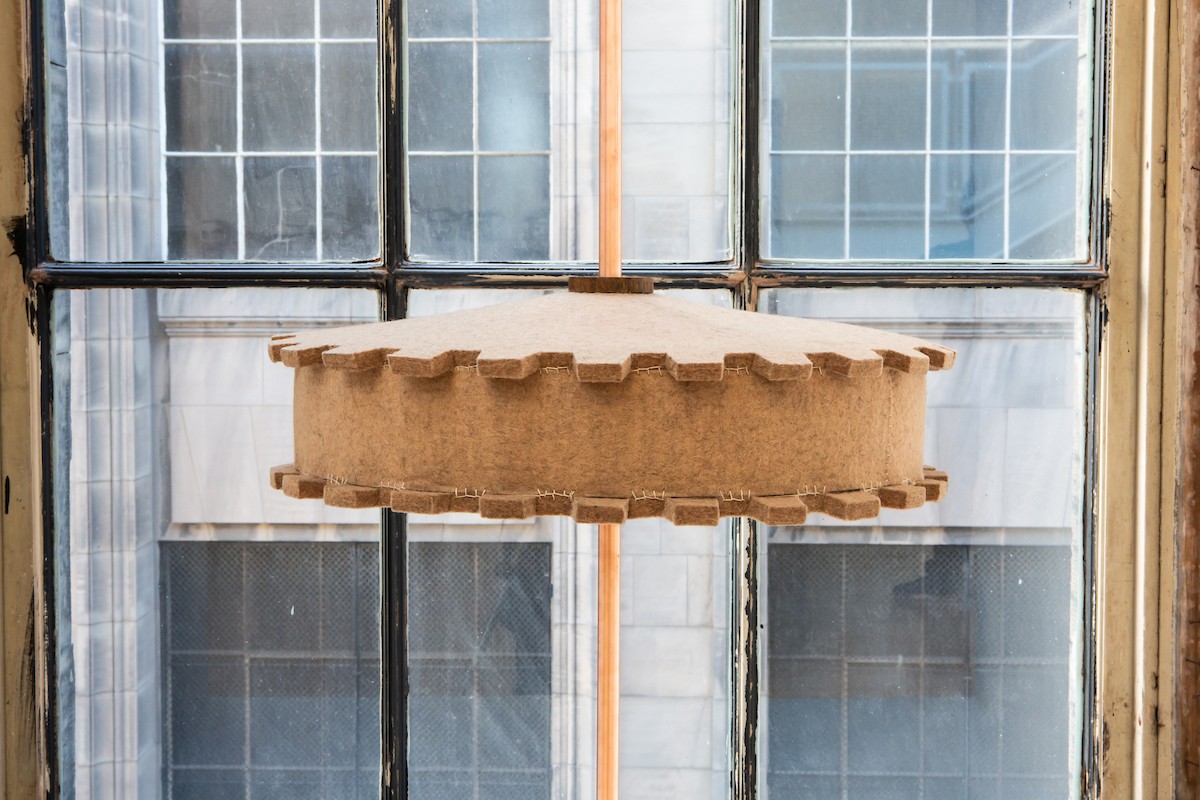

Johanna Unzueta

1:1 Resonance, 2020

Lantern Wheel A, 2017

Gemelos / Twins, 2017

Lantern Wheel B, 2017

Chilean artist Johanna Unzueta makes work in order to reconsider the relationship of people – their crafts, forms of resistance and rhythms – to the forces of industrialisation.

To her surprise, Unzueta began to introduce abstract drawing into her practice from the end of 2013. Creating cyclical forms, she was compelled by their proximity to patterns in nature, the looping forms made by children playing games (as featured in some of her film work) or the process of spinning threads. Distinct from modernist abstractions, they presented a method of choreographing her body’s movement to create a kind of index for how she was feeling at a particular time (she would title them with the date on which they were made). With her sculptural practice examining human labour and industrial objects they naturally evolved into large-scale murals.

For Unzueta – who is interested in traditional crafts – there is a close relationship between industrialisation and colonisation in the context of South America. Pre-Columbus, indigenous Mayan and Mapuche women made fabrics using a backstrap loom. Ancient Mayan artworks document women occupied by the looping, cyclical, whorling process of spinning naturally dyed cotton to make the required threads. The patterns of indigenous textiles are connected to particular families and localities, their weaving passing on a tacit knowledge from the ancestors. When the Spanish colonised South America they intended to replace these forms of production in order to increase profits by introducing sheep for their wool and semi-industrial looms. Like other colonial powers, this was part of a project to extend a capitalist European system of mechanised processes and standardised products. Part of a brutal system that would dominate the lives of oppressed people across the world, machines offered, in Unzueta’s words, ‘a new kind of slavery, a new method of human and economic abuse.’ But this system of modernisation was never total and in Guatemala, for example, women continue to use waist looms as a means of defiance.

Unzueta therefore recognises that forms which carry embodied memory can be used as a form of resistance. As she put it when describing her sculptural practice, ‘our bodies relate to space and they are in constant dialogue with the objects that compose it … they are part of an interest that has always been there, like a set of ephemeral memories that are subject to my interpretation of history.’

Remaking cogs and spindles and other machine parts is a process of reclaiming an aspect of modern history. The

sculptural works Lantern Wheel A, Gemelos / Twins, and Lantern Wheel B are all industrial components that have been handmade from felt. An ancient form of textile, felt is comprised of compressed wool fibres – which are randomly strewn in every direction – to form a material. Whilst often made from wool, the higgledy-piggledy structure of felt is very different from the linear forms produced on a loom. Deleuze and Guattari famously theorised this distinction when discussing ‘smooth’ and ‘striated’ spaces: spaces without specific boundaries or divisions – like felt – as compared to spaces with distinct lines, divisions and directions – like fabric made on a loom, production lines or plantations lines. To take machines apart and reform them in a material structurally opposed to straight lines is to remake the ‘ephemeral memories’ we might connect to them from a very different human perspective. Both the mural and the sculptural objects speak to the history of craft, something industrialisation was also responsible for separating from design in a move to rationalise production and create simple, specialist, mechanised roles for people. The tactile subtlety of Unzueta’s work therefore harbours a strong, embodied politics that attempts to re-humanise objects that have had such power to transform the material world.

Taryn Simon

Agreement to form a Palestinian national unity government, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, February 8, 2007, 2015

Finding Pursuant to Section 662 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as Amended, Concerning Operations in Foreign Countries Other than Those Intended Solely for the Purpose of Intelligence Collection, White House, Washington, D.C., United States, 1981, 2015

Taryn Simon exposes hidden systems of power and control, foregrounding in Paperwork and the Will of Capital the stagecraft and pageantry involved in the creation, maintenance and projection of state and economic power.

Prompted by an image of a flower arrangement positioned before Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler and Neville Chamberlain at the signing of the Munich Agreement (a meeting followed by Chamberlain’s ill-fated ‘peace in our time’ speech) Simon began to work with a botanist to identify and then reconstruct the flower arrangements appearing in archival photographs of the signings of political accords, agreements and treaties. Narrowing her remit, she decided to focus on those signings that included at least one country that had attended the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in 1944 (better known as the Bretton Woods Conference). This conference – which took place in New Hampshire in the United States – had established a set of rules for regulating the economy that led to the foundation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and, later, the World Trade Organisation. Encouraging open markets, privileging the US dollar and enabling international loans, this conference shaped the global economic system that would predominate in the second half of the twentieth century. Criticism of the IMF and World Bank – both of which have outlasted the Bretton Woods system – has centred upon the manipulation of world markets, harsh restrictions imposed on ‘debtor’ countries and the encouragement of privatisation at the expense of the world’s poorest people. Simon’s decision to engage this history in Paperwork and the Will of Capital was therefore a decision to focus on the power play and interventionist approaches of countries with stakes in the process of globalisation.

A second parameter Simon set for the project was to focus only on agreements signed after 1968. The significance of this date was the opening of the international flower market in Aalsmeer (the Netherlands), which remains the largest flower market in the world (moving around 20 million flowers per day). This market created the opportunity for people to buy any kind of flower at any time of the year – in bloom!

Another historical connection to the Netherlands that Simon was interested in pertains to a genre of still-life painting. In the eighteenth century, Dutch artists would demonstrate their skill by painting flower arrangements. However, these paintings were not based on reality. Artists like Jan van Huysum (1682-1749), for example, would paint up to 30 different species of flowers into a single image – including non-native species and flowers that would never be in bloom in the same place at the same time – to create an ‘Impossible Bouquet’. In effect, all the arrangements appearing in Simon’s works are Impossible Bouquets, made possible only by advances in cultivation or the vast imports of markets like Aalsmeer.

Like the other 34 works in the series, the two featured in Pine’s Eye are high-definition photographs of the bouquets that Simon reconstructed in her studio. Each bouquet is set against a colour-field with a palette based on the colour scheme of the room in which the corresponding agreement was signed. Set into each mahogany frame is a text panel detailing the agreements that a particular bouquet bore ‘silent witness’ to, in Simon’s terms. In this case they detail: Ronald Reagan’s reauthorisation of covert CIA activities in Afghanistan to back rebels (including Osama Bin Laden) and a 630 million dollar weapons investment to repel Soviet forces; an agreement between Hamas leader Khaled Meshal and Fatah leader and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas to form a national unity government and end violence between Palestinian factions. Withholding as much as they reveal, Simon’s works carry a poignancy related to the volatile or fragile nature of political agreements. In the case of the Hamas/Fatah agreement, for example, peace lasted just four months after the signing of the treaty. The ephemeral beauty of flowers evokes the fragile and temporary nature of human relationships.

Beau Dick

Otter Woman, 2016

Tsonoqua, 1980

Respected Kwakwaka’wakw Chief, indigenous rights activist and carver, Beau Dick (1955–2017) used his great skills as an artist to try to protect, preserve and share his ancestral knowledge.

The Kwakwaka’wakw have a deep cultural connection to nature, with families tracing their history back to ancestors

who gained special powers from supernatural birds or animals. These powers are carried by bloodlines and allow initiated members to perform particular stories, dances and rituals. Chief Beau Dick (Walas Gwa’yam or ‘big, great whale’) is from Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, where such performances take place within the sacred space of the Big House. This painted building appears like a giant figure that swallows people as they enter through its grinning mouth; whilst suggesting the cycle of life – as things are consumed and then reborn from inside – the mouth motifs that appear in much Kwakwaka’wakw art reflect the belief that hunger is at the core of the human condition. In light of this belief, it is a culture that emphasises gift giving, respect for life and self-control, against the evils of an unchecked appetite.

These evils might be represented by terrifying creatures, with tricks – like smoke and hidden doors – being used within the Big House to make them extra frightening. Children are told that the sound of the wind blowing through the cedar trees is the breath of Tsonoqua, a giant, lumbering, mythical being depicted with black skin and huge red lips. Her house is full of great treasures – such as ‘coppers’ (copper beaten flat, the most important symbol of wealth) – to lure children into the woods. If they are not careful they will be snatched by Tsonoqua and put in her basket to be eaten later. Otter Woman is a shapeshifter who can trick people into thinking that she is a friend or relative whilst really taking them into the precarious spirit realm.

In Kwakwaka’wakw legends, it is believed that otters evolved from humans, which gives them a special understanding of both worlds.

Seeing his people (living in the area now designated British Columbia) as victims of cultural genocide*, Dick recognised that his culture could offer vital forms of critical resistance against the modern world. Inspired by the Idle No More movement, an indigenous protest against the despoiling of their lands, the poisoning of their waters and destruction of plants and animals (through the mining, logging, oil and fishing industries), Dick led a march against the Canadian Government. Culminating in Ottawa, Dick performed a breaking of the ‘copper’ ceremony outside parliament in order to shame the government for its treatment of the environment and indigenous people. Smashing the ‘copper’ is a potent symbol of great discontent with another’s actions.

For Dick, his role as an artist was to share Kwakwaka’wakw ideas about how to care for nature and for humankind. In an interview in 2015 he said:

As an artist, it is my responsibility to restore and preserve the culture. Why? Because it is our identity. The impact of colonialism and cultural genocide continues. We’re working very hard and struggling to ensure that we keep it real in this world of convenience. Others may cater to and serve industry ... but there’s another world that’s ... much more valuable and it’s all about connectedness, not only to the mother earth, not only connectedness to the great Creator but indeed it is about connectedness to each other. This is the overall message we want to illustrate. This is what our culture provides for us and illustrates in so many ways.

* Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded its report on the effects of the Indian Residential Schools System that the impact on Indigenous people amounted to cultural genocide.

Firelei Báez

I write love poems, too (The right to non-imperative clarities), 2018

Dominican-American artist Firelei Báez draws upon African- diasporic mythologies, folklore and global political movements to create a visual language of resistance and healing that opens historical narratives up to new future possibilities.

With her mother being from the Dominican Republic and her father from Haiti (countries that share the island of Hispaniola and have often been in conflict since their division by French and Spanish colonists) and moving to Miami as a child, Báez is acutely aware of the racial hierarchies that people in these regions are subjected to – hierarchies of skin colour, hair and body types. These divisions relate to nature too: Báez recalls the verdant landscape of the Dominican Republic compared to the despoiled landscape of Haiti, which has now been deforested to the point where it stands to lose all its forest within two decades. From the vantage point of being, in her terms, a ‘Caribbean hybrid,’ Báez has developed a repertoire of powerful figures and emblems that she can deploy against systems of oppression, tying them together with a forward- looking science-fictional inflection.

One recurring emblem is the Tignon, a headdress that black women living under Spanish rule in eighteenth century Louisiana were forced to wear as part of an attempt at policing their bodies. Ingeniously, these women adorned them with vibrant patterns, ribbons, broaches and beads as a means of self-empowerment, becoming a fashion statement that was subsequently adopted in other parts of the world, and that in effect undermined the restrictions. The use of the Tignon in Báez’s work acknowledges a painful history while celebrating resilience and the assertion of individual identity. Many of

Báez’ shape-shifting figures seem to be possessed by bright, patterned forms, a sign of colourful defiance and vibrant, sexual, untamed sprits. Sometimes involving serpentine forms they also reference Ayida-Weddo, a voodoo spirit of fertility, rainbows, wind, water, fire and snakes, who is known to hold the key to higher knowledge.

Another recurring motif is the Ciguapa, a mythological creature from Dominican folklore who is covered in black fur. With feet pointing backwards so she is almost impossible to track, she

is the ultimate trickster. Against conventional readings that demonise her for fear of her autonomy and continuity with nature, Báez depicts her as wild and untamed, or in her words, as a ‘total badass’. She often depicts her as a part botanical hybrid who channels the energy of nature. Other symbols include: a black pendant taking the form of a closed fist with thumb held between two fingers known as an azabache, which protects against the evil eye of envious onlookers and images from more contemporary protests including the clenched fist of solidarity and stone throwers, international symbols of rebellion.

'I write love poems too (The right to non-imperative clarities)' is part of a body of work Báez made by applying these motifs onto the pages of specific books. Whether decommissioned from libraries (perhaps wanting to rid themselves of troubling colonial narratives) or second hand bookshops in New Orleans (a city connected to the sugar trade running through the Caribbean), Báez finds interest in details that evoke a particularly Western view. The selected maps, diagrams and charts all speak to her of sterilised or rationalised relationships and hierarchies. As Báez states, ‘the language in the organisation of space in our buildings and communities reflects and reinforces social relationships conditioned by gender, race and class, strengthening some groups over others and perpetuating inequality. So as an artist, I set out to create my own language of perception to question some of the contradictions inherent in the history of landscape.’ Beginning with colourful poured paints that suggest a free and powerful energy, that then morphs into specific characters and symbols, Báez has created a practice that spans archaeology, folklore and science fiction, intervening into historical records to awaken other future possibilities.

![Munoz La cabeza mató a todos [The head that killed everyone], 2014](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image/public/2020-03/lacabezamatoatodos.jpg?itok=gEE-fti0)

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz

Farmocopia, 2013

La cabeza mató a todos [The head that killed everyone], 2014

Gosila, 2018

Matrulla, 2014

Black Beach/Horse/Camp/The Dead/Forces, 2016

Puerto Rican film-maker Beatriz Santiago Muñoz creates films that explore the effects of colonialism, military testing, industrialisation and tourism on her country’s landscapes.

Muñoz’ documentary films come about through an interaction with people and places, rather than through a predetermined process. Against Western values such as originality, linearity, purity and presence, they focus on aspects of life that are adapted, cyclical, hybrid and happening. These values relate to the complex way that ecologies develop, the complex creole culture of Puerto Rico resulting from Spanish colonial rule, the slave trade and the displacement of indigenous Taíno people, and to its equally complex botanical habitat following Spanish colonisation. Muñoz’ commitment to resist the stereotype of Puerto Rico as an unspoilt exotic paradise shows that what the Spanish once thought of as ‘The Island of Enchantment’ has been terribly exploited. The selection in Pine’s Eye focuses on the coexistence of people, plants, science and magic in this ever-transforming context.

Farmacopea takes its title (in English pharmacopoeia meaning ‘drug making’) from a catalogue of plants and their uses. Whilst offering an inventory of sorts, listing extant native species, Muñoz’ film is irresistibly drawn into the stories that surround this potent flora. The Manchineel tree, for example, is so poisonous that just being near it can lead to permanent blindness; its ‘little apple of death’ seducing and killing many foreign sailors.

La cabeza mató a todos (The head that killed everyone) takes its title from a local myth in which a shooting star was reinterpreted as a head without a body raging chaos across the land. Filmed in a post-industrial Afro-Caribbean area of Puerto Rico called Carolina, and mixing natural sounds with ‘60s Peruvian punk music, the film blurs time, just as it imagines a spell capable of challenging the military industries that have so damaged the island. Mapenzi Chibale Nonó – a local cultural activist who has an interest in botany – appears in the film as if a kind of vessel for these dark ambiguous forces.

Gosila is the most recent of Muñoz’ works in Pine’s Eye. The title is the caribbeanisation of Godzilla and it was filmed in the aftermath of a huge storm that hit Puerto Rico in 2017. Hurricane Maria was the largest ever recorded in the Caribbean and

was one of the worst natural disasters in the island’s history. It resulted in food and water shortages, power outages and the closing of hospitals. However, Gosila carries with it a peculiar sense of tranquillity and unease as people do what they can

to recover the island – and animals are seen returning to their natural cycles – as if the rigid patterns of modern life

are at once to blame for freak weather and disrupted by its apocalyptic effects.

Matrulla revisits the place of Farmacopea, but this time Muñoz introduces us to Pablo Diaz Cuadrado, the last remaining member of a commune set up in 1968. Cuadrado lives near Lago Matrullas, a reservoir in the region. Maintaining the plants, bees and structures around him, Cuadrado prepares for a future with no food or water. Informed by his experiences of psychoactive drugs, he describes episodes of time travel which lend to the film a sense of moving through different realities at once.

Black Beach/Horse/Camp/The Dead/Forces is set on a black magnetite beach on the small Puerto Rican island of Vieques where the US conducted military testing for 60 years. This testing has led to the suspected illnesses of many of the island’s inhabitants. Within this film we see a man who looks after horses, an artist who helped to resurrect a sacred tree previously on the naval base and a man who performs rituals intended to maintain a ‘cosmic balance’. The film alludes to the effect of forces at play in the balance of nature.

Torsten Lauschmann

TOPIARY JIG, 2020

Torsten Lauschmann carefully choreographs and automates objects, audio and images to explore speculative narratives, his new work TOPIARY JIG questioning the fragility of the human body by ritualising the objects intended to assist it.

Building on his 2018 Glasgow International work WAR OF THE CORNERS, Lauschmann utilises a strategy from science fiction to project back from an imagined transhuman future where bodies are radically enhanced by technology. Continuing a critique of what he considers to be naïve assumptions about how we might transcend our physical limitations, Lauschmann asks, what might objects presently used to support fragile or impaired bodies become?

Through the choreography of a multisensory installation, Lauschmann allows the answer to be led by fragmented, layered and sensorial elements. Mobility aids, wedged between the floor and ceiling, give the architecture of the space a sense of precarity: as if they are bespoke measures that have become necessary to keep the institution itself intact. An individual’s aid in our present reality, in this other dimension they seem to implicate anyone entering the space. Lauschmann is concerned by austerity, privatisation and the erosion of the welfare state, and he sees the objects as metaphors for a culture of care. The chopped mobility aids, are, according to Lauschmann, dancing a Dance Macabre in a courtly nationalistic fashion. With the effects of lighting and sound the movement of some of the disability aids follow a kind of obscure automated ritual that seems to imply that they have a life of their own, or at least some animating energy that connects them to a higher purpose.

Coupled with the all-at-once impact of Lauschmann’s practice this is evocative of a recent development in philosophy

called speculative realism, which stresses that there is no true hierarchy between humans and other kinds of objects. Summarising an aspect of the work of Alfred North Whitehead – a critical precursor to this movement – Steven Shaviro writes, ‘[In] Whitehead’s own terms, Western philosophy since Descartes gives far too large a place to “presentational immediacy”, or the clear and distinct representation of sensations in the mind of a conscious, perceiving subject. In fact, such perception is far less common, and far less important, than what Whitehead calls “perception in the mode of causal efficacy,” or the “vague” (nonrepresentational) way that entities affect and are affected by one another ...’.

Speculative in this sense, Lauschmann seems to be aiming to describe a reality that sits beyond this ‘presentational immediacy’. Some of the crutch supports hold camera phones that feed live images back onto the walls of the space, creating a feedback loop: forming echoes and ripples. This deviates from the kind of linear time that characterised modernity by instead emphasising the coexistence of past, present and future moments. With a walking frame hooked up to microphones to become a kind of wind chime, and the percussive effect of the moving disability aids (some with bells attached, like morris dancer’s), there is also a sense that these objects have become musical instruments; rhythm and sound adding another layering of moments.

Lastly, digital images of computer generated topiary tree forms keep trying to establish themselves in the space, only to be cut back by a rigid grid of laser lines. Whist modern thinking tends to separate digital technologies from the past and from nature, here they seem to be part of the same non-hierarchical system that sees humans and objects on the same level of being. Topiary is the deliberate inhibition of the natural growth of trees and shrubs to create sculptural representations; jigs can describe the set movements performed in some morris dances but can also describe a fixture for guiding a machine tool towards an ‘arrested’ object, especially for locating and drilling holes. Together, TOPIARY JIG seems to suggest these seemingly prescribed forms carry with them a certain capacity for transformation: a ritual becoming between people, objects and nature.

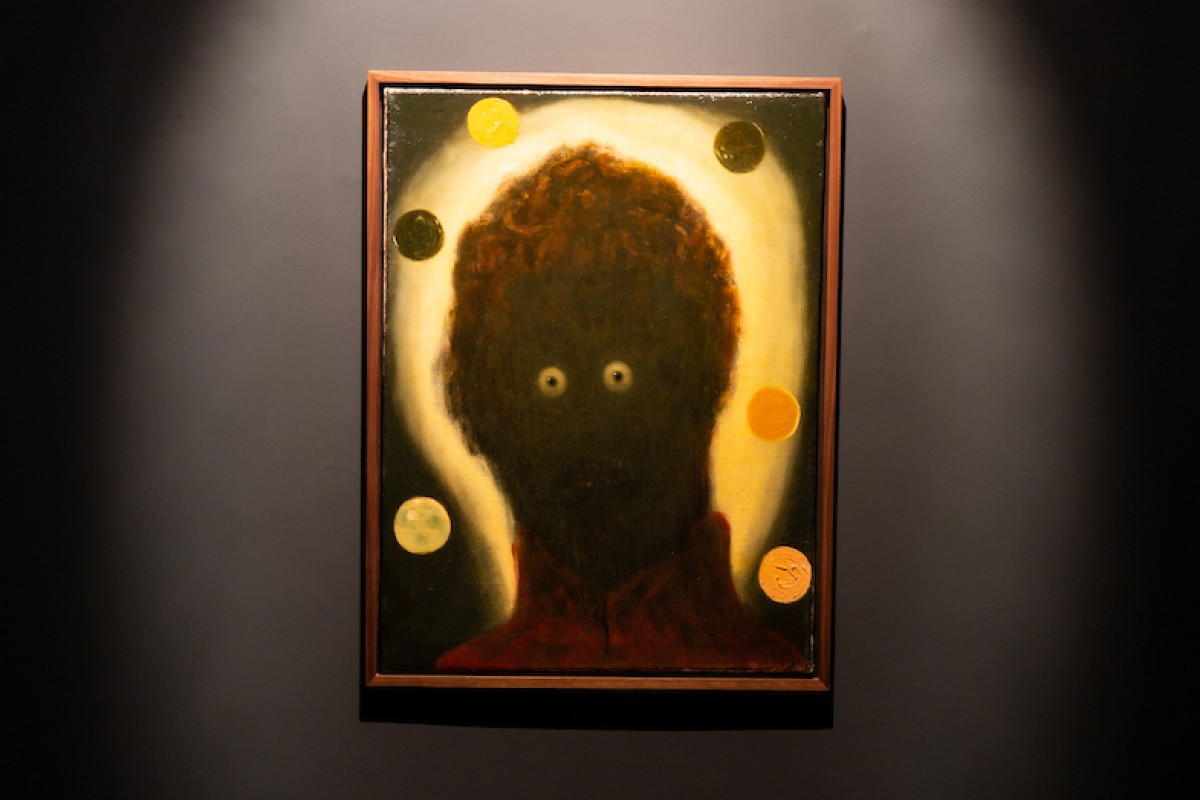

Kevin Mooney

Apparition, 2018

Orbs, 2018

Trickster, 2017

Peasant, 2018

Cork-based artist Kevin Mooney makes paintings that speculate about connections between the folk cultures of Irish émigrés and the cultures of the Caribbean, and their absence from Ireland’s art historical record.

On taking control of Jamaica in 1655, England – at that time ruling Ireland – displaced large numbers of Irish people to Jamaica to raise the colony’s population and increase its labour force. Some, considered undesirable, were forcibly displaced, some were kidnapped, and many migrated as indentured servants to work on the English sugar and tobacco plantations (signing an agreement to serve a master for a number of years, in return for passage). Many died on the crossing or later from the poor working conditions: they were nicknamed the ‘red legs’ on account of the effect of the climate on their fair skin, and in later years English political leader Oliver Cromwell preferred to send children, who he believed would have a better chance to adapt. Such was the impact of this process that today 25 percent of Jamaicans claim Irish ancestry. It is a story that extends across other Caribbean islands including Barbados and Montserrat, and one that speaks of the coercive uprooting of people from their traditions and lands.

During this period the Irish population dropped significantly (by around one third owing also to famine and conflict) and from an Irish perspective this history of emigration is one of great loss, as many people went away never to return. For Mooney, as a painter trying to connect with the visual history of Ireland, the seventeenth century is something of a void within the records. For him, English rule led not only to mass migration but also to a kind of exodus of cultural memories, identities and traditions. He states that, ‘when a visual culture does re-emerge in the eighteenth century in Ireland it is only within the context of a complicated, contested and compromised history emerging under colonial rule. So, engaging with this earlier period of Irish history through art involves a leap of the imagination.’

Apparition, Orbs, Trickster and Peasant – appearing at intervals throughout the exhibition – invite us to take this leap of

the imagination. Occasionally including motifs that appear like straw, they reflect traditions like the ‘Straw Boys’ from Ireland and comparable folk traditions and crafts carried by West African slaves to the Caribbean; threads tracing back to more pagan traditions rooted in nature. But these mischievous spectres also appear broken and torn. Mooney, in fact, considers them less as portraits – as representations of someone’s status and individual personhood – than as gruesome trophies. Here he references, ‘early Celtic traditions where the head is considered the site of knowledge, consciousness and spiritual power, to the point that the decapitated head of one’s enemy was considered a prized possession. [Where] to possess it meant possessing everything they saw or knew as well as their spirit and energy.’ This gives them another kind of charge. Out of the obscurity of darkness, the eyes appear hypnotic and compelling, seemingly beseeching us to find a way to look beyond the surface. As Mooney includes loose reference points to images by painters like Paul Henry (see Apparition) or photographer John Hinde (see Trickster), who in the early twentieth century produced romanticised images of Ireland’s soft landscapes, gentle people and bucolic country settlements, we might consider this surface to be what remains when the violence of history is expunged by those in control. In this way, Mooney sets up his works to haunt us; hybrid, partial, zombie figures that – unhinging the usual stability of the portrait - challenge us to see what they have seen, or at least be prepared to imagine.

Laurent Grasso

Studies into the Past, 2017 - 2019

OttO, 2018

Laurent Grasso unsettles traditional narratives of time and progress, on the one hand through his painstaking Studies into the Past that disrupt our sense of linear progress, on the other by representing the energy fields of aboriginal lands.

The Swiss historian of art Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897) invented many of the early ideas associated with the Renaissance (the present meaning of the term also invented in the nineteenth century). On the subject of global exploration, he wrote, ‘The true discoverer ... is not the man who first chances to stumble upon anything, but the man who finds what he has sought. Such a one alone stands in a link with the thoughts and interests of his predecessors....’ Accommodating the ideas of artists working in this period about the superiority of perspective and rational observation, these nineteenth century accounts created a separation of people from nature and particular ideas about visual representation.

To create Studies into the Past, Grasso drew on scientific analysis to learn the painting techniques of the fiftheenth and sixteenth centuries. In this way he was able to work through the visual language of the Renaissance in order to manipulate the associations connected to it. Creating an alternative ‘false historical memory’ his paintings show familiar visual schemes interrupted by inexplicable phenomenon that ask us to question what it is that we seek.

Given the centrality of observation in the Renaissance it is not surprising that eyes appear frequently in these works. Where perspective privileged the single eye of the artist and made the spectator the centre of the world, in Grasso’s paintings eyes spawn across surfaces to break the window onto the world, intruding upon the objective safety the spectator might feel. In other cases what would typically be religious phenomena are replaced by physical phenomena like floating rocks. As Jason A. Josephson-Storm has argued in his book The Myth of Disenchantment, the European idea of modernity relies upon the idea of a break from magic that in fact never took place. In another painting, spherical objects appear like strange inexplicable, geometric spectres across a landscape.

These spheres come from Grasso’s film OttO. Continuing to question how we represent different forms of knowledge

this film considers the energies of ancestral sites. Captured with drones, using thermal (heat) and hyperspectral (wide frequency spectrum) cameras across Aboriginal sacred sites that are thought to connect the living to the ancient past, the film presents various modes of looking whilst the spheres become the abstract carriers of secret stories. Jakurrpa is a very important concept in the Warlpiri culture and belief system – ‘dream time’ or ‘the dreaming’ being the ‘grossly inadequate English translation’ as Dr Christine Nicholls, Senior Lecturer in Australian Studies at Flinders University, puts it. It embraces a non-linear time that is at once past, present and future. Nicholls writes, ‘Dreaming Narratives also have encoded in them important information regarding local micro-environments, including local flora, fauna and the location of water, deep knowledge of “country”, and survival in specific locations.’ In this context the spheres invite the viewer to acknowledge what we cannot know by observation alone or as phrased in the exhibition guide at Galerie Perrotin, that ‘a stranger’s vision can only be fictional.’ OttO is named after both the traditional owner of this landscape, Warlpiri elder Otto Jungarrayi Sims, and German physicist Winfried Otto Schumann (1888–1974) who predicted low frequency signals caused by radiation in the atmosphere. Bringing together these different perspectives on invisible energies, Grasso intentionally creates a tenuous territory between types of knowledge that are often considered irreconcilable, relishing the points at which it is hard to establish a singular truth.

Lois Weinberger

Selected works on paper

Invasion, 2009

Austrian artist Lois Weinberger has spent a lifetime cultivating plants in the wastelands (plants termed ruderals) in a way that deconstructs some of our false ideas about what and where nature is.

Weinberger’s work often exposes how our understanding of nature is tied up with other problematic cultural values. For example, introducing neophytes (in botany: invasive foreign plants) into European cities in the 1990s, he used plants to reflect attitudes to immigration (See What is beyond plants is at one with them, a representation of his plantings in a disused parochial train station for documenta X, Kassel, 1997). ‘Weeds’ are denied status because they are seen to invade sites not designated for ‘authentic’ nature, whilst also not conforming to our idea that ‘real’ nature is comprised of native species alone.

In her book Rambunctious Garden, Emma Marris shows how our ideas of authenticity and a ‘pristine wilderness’ developed

in the nineteenth century with early conservation movements that hinged on ideas of preservation, beauty and purity (considered a lack of human intervention). But the issue is that nature is always in transition so there is no static point to return to and maintain; areas of biodiversity are often not considered attractive (swamps for examples); and there are no places on earth that are ‘untouched’. Millions of indigenous people have been cleared from lands to make way for natural parks, yet they harmoniously tended to them for thousands of years. In her 2016 TED talk Marris said, ‘if all ... the definitions of nature that we might want to use ... involve it being untouched by humanity or not having people in it, if [they] give us a result where we don’t have any nature, then maybe they’re the wrong definitions. Maybe we should define it by the presence of multiple species, by the presence of a thriving life.’

In this context, Weinberger’s works in wastelands can be seen to be prescient signs of how attitudes need to change. Against ‘pristine nature’ Weinberger argues that the best gardeners are those who abandon their gardens, because structure and neatness is the antithesis of nature. Moreover, by cultivating in-between the cracks in pavements (External Areas, 1996) or soil in synthetic shopping bags (Portable Garden, 1994) he emphasises that the effects of nature are everywhere, and cannot be excluded from urban spaces. He terms his interventions ‘perfectly provisional areas’, creating projects that are, in a sense, falling apart as they are made. His distinction between the visible effects of nature – which inform many of our false interpretations of it – and the real, invisible, multiple and cyclical processes that underlie it, is also important for our understanding of his enigmatic works on paper. Where aesthetic objects use symbols to construct concepts of nature, Weinberger wants to evoke that which stands outside such representations. His drawings for future gardens, wilderness gardens or underground gardens, highlight a way of working that is distinct from planning. Avoiding clear spatial models they utilise chance elements and tangles of lines to suggest unruly connections without clear edges or boundaries.

Invasion (real tree fungi spray-painted with luminous paint), is at once a strange intrusion into the space and conventions of the gallery and a clearly synthetic encounter. As Anna Tsing argued in Mushroom at the End of the World, mushrooms flourish in the failing zones of capitalism and epitomise multispecies survival in ruined landscapes. Like strange way finders, they remind us – with Weinberger’s broader practice – that to better the environment, we must learn to drop preconceptions about a pristine nature and accept contamination, transition and compromise.